High-Speed Rail and Local Agricultural Development

We study China’s extensive high-speed rail (HSR) expansions to address a key policy concern that large-scale transport infrastructure may undermine agriculture and food security. We find that HSR expansion facilitates the outflow of labor and land from agriculture, yet does not reduce agricultural output because productivity rises.

Large-scale transport infrastructure has become a cornerstone of development strategies worldwide, with China’s high-speed rail (HSR) network standing as the most prominent example. By the end of 2021, China had built more than 40,000 kilometers of HSR, accounting for approximately two-thirds of the world’s HSR tracks. This expansion has dramatically reduced travel times, reshaped urban hierarchies, and deepened regional economic integration. Yet alongside these achievements, a growing policy concern has emerged: does HSR undermine agricultural development by accelerating labor outflows and farmland loss?

These concerns are well grounded. Substantial literature shows that improved transport infrastructure can facilitate the migration of agricultural labor into off-farm employment (Asher and Novosad 2020, Morten and Oliveira 2024) and reduce cropland both directly through construction and indirectly through urban expansion (Baum-Snow et al. 2017). In China, where agricultural labor has declined rapidly and pressure on arable land is persistent, such dynamics raise particular concerns for food security and rural agricultural development. Yet the aggregate evidence presents a striking puzzle. Despite rapid labor outflows from agriculture and continued urban expansion, China’s agricultural output has remained broadly stable over the past two decades. This raises an important policy-relevant question: can large-scale transport infrastructure coexist with sustained agricultural production, and if so, through what mechanisms?

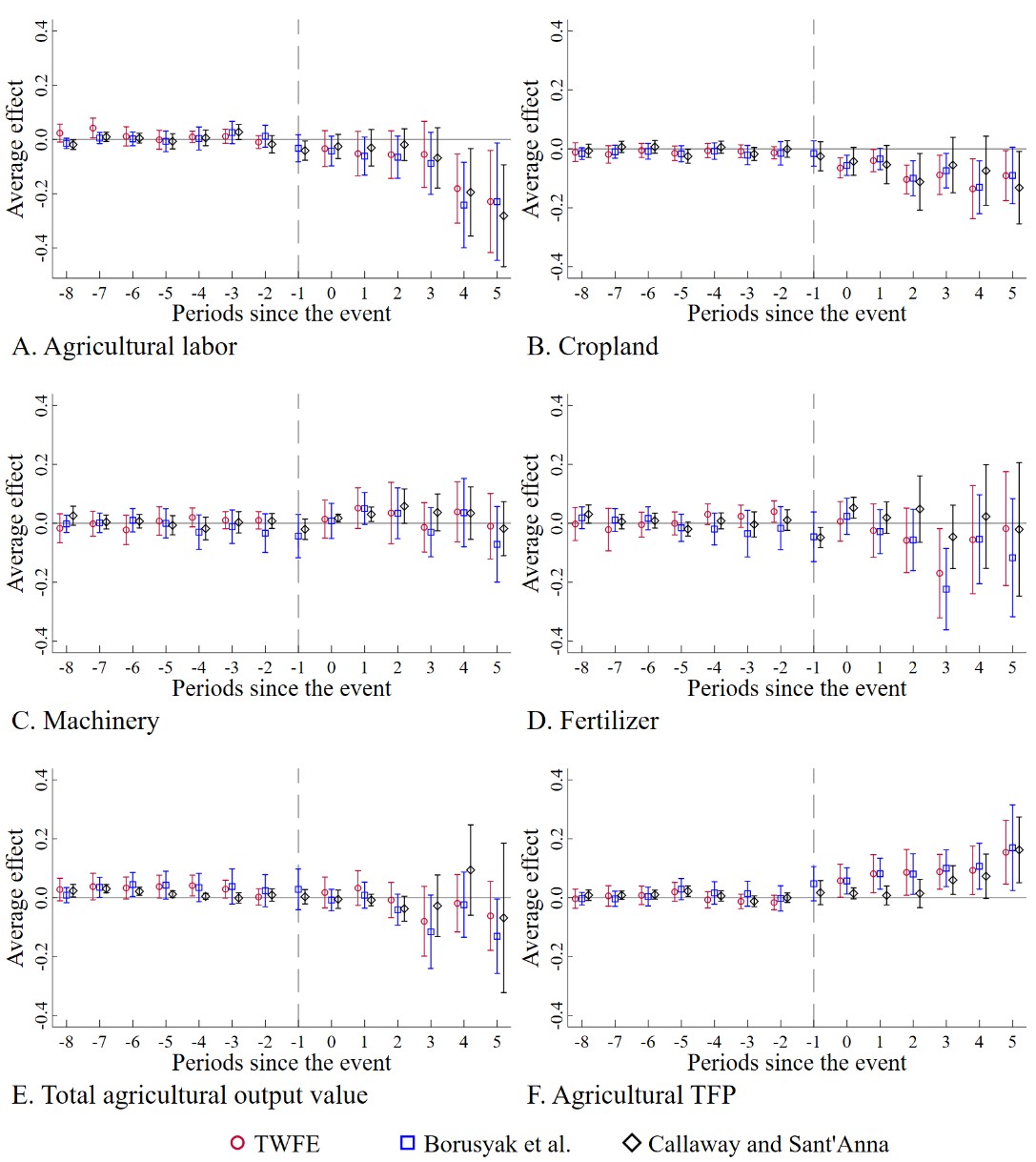

In our study (Chen et al. 2026), we address this puzzle by examining how access to HSR affects agricultural development in rural China. To establish causation, we exploit the staggered rollout of HSR stations across locations as a quasi-natural experiment. Using county-level and household-level data, we estimate a staggered difference-in-differences approach that uses unconnected rural counties as the control group and defines treatment cohorts based on the year of HSR station opening. Figure 1 summarizes the dynamic effects of HSR connectivity. After gaining HSR access, rural counties experience significant reductions in agricultural labor and cropland (Panels A and B), especially in underdeveloped regions characterized by low GDP, inadequate transport infrastructure, and heavy reliance on agriculture. Despite these declines in inputs, however, we find no evidence that HSR access reduces total agricultural output (Panel E).

Importantly, the resilience of agricultural production appears to stem from productivity gains. Figure 1 shows that HSR access has no statistically or economically significant impacts on fertilizer use, and the total number of agricultural machines (Panels C and D). In contrast, agricultural total factor productivity (TFP) rises significantly following HSR access (Panel F), effectively offsetting the negative input effects. Our estimates suggest that HSR connectivity increases county-level agricultural TFP by approximately 4.9–7.8%. These results are robust across alternative methods employed to calculate TFP and when TFP is computed using household-level data.

Figure 1. Dynamic impacts of HSR.

Notes: This figure shows the dynamic impacts of HSR on key outcomes using various DiD estimation approaches. Year = 0 represents the year of initial HSR connections. Year = -1 denotes the year prior to HSR connections and serves as the baseline for comparison. Circles, squares, and diamonds in each panel correspond to estimates from TWFE, Borusyak et al. (2024), and Callaway and Sant’Anna (2021), respectively. Whiskers represent 90% confidence intervals.

To ensure that these findings are not driven by non-random HSR placement or modeling assumptions, we conduct a series of robustness checks using alternative CSDID estimator and instrumental variable approach. Specifically, we use three instruments: i) the layout of China’s historical railway network in 1961; ii) hypothetical least-cost path spanning tree networks; and ii) recentered market access growth, constructed following Borusyak and Hull (2023). Across all specifications, the results remain stable: HSR access reduces agricultural labor and cropland, but raises productivity enough to sustain agricultural output.

We then explore the channels through which HSR access raises agricultural TFP. HSR connectivity boosts local GDP and government revenue in connected rural counties, primarily due to the growth in industrial output. Thanks to the “Industry Nurturing Agriculture” policy, these gains are partly channeled back into the agricultural sector through providing financial assistance to rural households and collectives, increasing investments in agricultural infrastructure, and improving rural road infrastructure. At the same time, lower transportation costs associated with HSR access facilitate farmers’ participation in technical training and encourage the establishment of new agribusiness firms. Household-level evidence further shows that farmers in HSR-connected areas increasingly rent agricultural machines to cope with reduced labor, and shift toward higher-value agricultural production. By improving farmers’ access to larger and more profitable markets, HSR connections raises returns to agricultural production, thereby strengthening farmers’ economic incentive to invest in productivity-enhancing practices. Together, these factors contribute to the overall improvements in agricultural TFP.

These findings carry important policy implications. They suggest that large-scale transport infrastructure need not undermine agriculture, even in economies undergoing rapid urbanization and industrialization. When embedded in a supportive policy environment, HSR can facilitate structural transformation while sustaining agricultural productivity and food security. The key challenge for policymakers is not to resist the reallocation of labor and land, but to manage these transitions in ways that promote productivity and long-term agricultural resilience. These lessons are especially relevant for developing countries, given their continued dependence on agriculture and the projection that most future global land transport infrastructure will occur in these nations.

References

Asher, Sam, and Paul Novosad. 2020. “Rural Roads and Local Economic Development.” American Economic Review 110 (3): 797–823. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20180268

Baum-Snow, Nathaniel, Loren Brandt, J. Vernon Henderson, Matthew A. Turner, and Qinghua Zhang. 2017. “Roads, Railroads, and Decentralization of Chinese Cities.” Review of Economics and Statistics 99 (3): 435–48. https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00660.

Borusyak, Kirill, and Peter Hull. 2023. “Nonrandom Exposure to Exogenous Shocks.” Econometrica 91 (6): 2155–85. https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA19367.

Borusyak, Kirill, Xavier Jaravel, and Jann Spiess. 2024. “Revisiting Event-Study Designs: Robust and Efficient Estimation.” Review of Economic Studies 91 (6): 3253–85. https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdae007.

Callaway, Brantly, and Pedro H.C. Sant’Anna. 2021. “Difference-in-Differences with Multiple Time Periods.” Journal of Econometrics 225 (2): 200–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2020.12.001.

Chen, Xiaoguang, Binlei Gong, Zhilong Qin, and Xiaoli Wang. 2026. “High-Speed Rail and Local Agricultural Development.” Journal of Development Economics 179: 103647. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2025.103647.

Morten, Melanie, and Jaqueline Oliveira. 2024. “The Effects of Roads on Trade and Migration: Evidence from a Planned Capital City.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 16 (2): 389–421. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20180487.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email