Debt Management and Strategic Interactions in Top-down Bureaucracy: Evidence from China

The Chinese central government implemented a series of measures to establish a top-to-bottom debt ceiling management system starting in 2015. Under this regulatory framework, public debt issuance for a prefecture city is subject to a ceiling (quota) determined through a hierarchical procedure. Based on a comprehensive dataset, we investigate what factors determine the allocations of debt ceiling to prefectural cities in China after the debt management reform. We find that the distributional outcome of the debt ceilings relies on the bilateral interactions of local and their superior governments. We also estimate the effect of ceiling allocation on the real economy, as well as the potential risk associated with implicit debt accumulation.

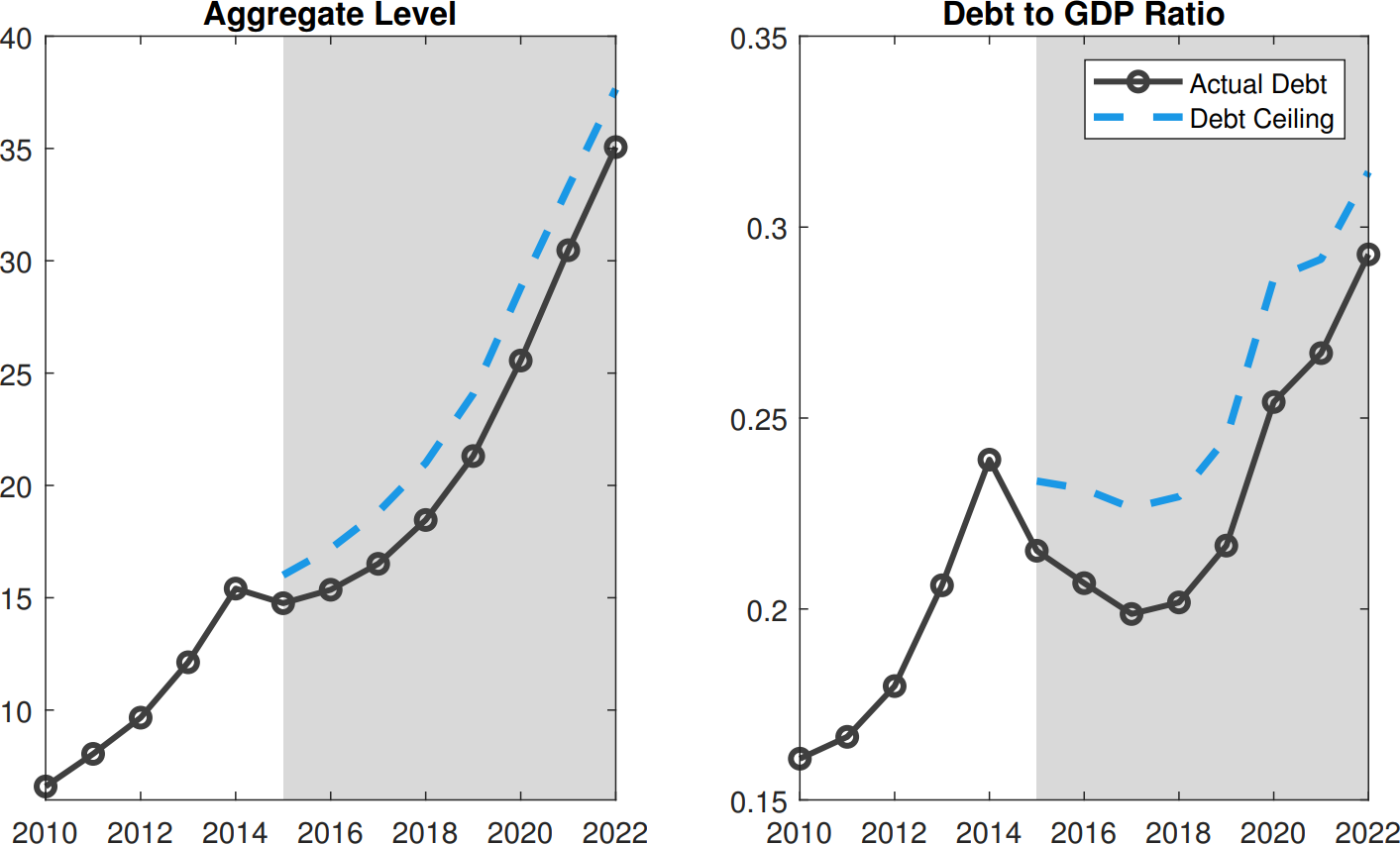

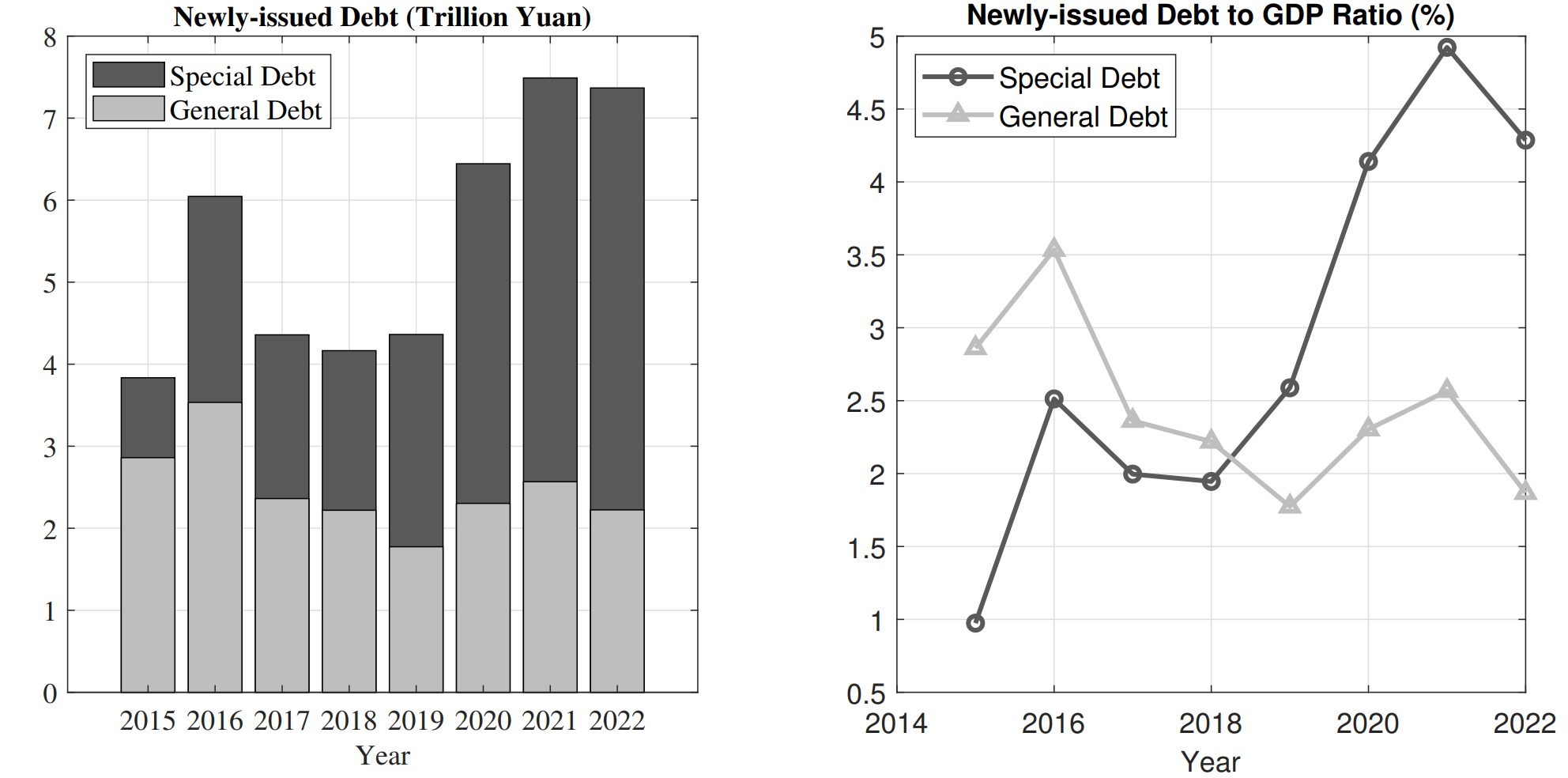

The surge in local government debt has become a critical factor driving the leverage boom and the expansion of the shadow banking in China (Zhang and Barnett, 2014; Bai et al., 2016; Song and Xiong, 2018; Chen et al., 2020). Being aware of potential financial risks, China’s central government issued several regulations pertaining to the management of local government debt since 2014. In December 2015, the Ministry of Finance (MoF) issued Opinions on the Implementation of Ceiling Management for Local Government Debt, which establishes a top-to-bottom debt ceiling management system to strictly control the ceiling on local government debt. Under this regulatory framework, public debt issuance for a prefecture city is subject to a ceiling (quota) determined through a hierarchical procedure. Figure 1 presents China's aggregate debt stock since 2010 and debt ceiling since 2015. The figure shows that starting in 2015, the outstanding explicit debt is strictly below and follows the trend of the debt ceiling. This suggests that the accumulation of official local government debt is determined by the tightness of debt ceilings after the policy reform. Notably, our measure particularly refers to the so-called explicit local government debt and does not contain the implicit local government debt or the liability of local government financing vehicles (LGFV) that the local government implicitly guarantees.1

Figure 1. Actual Debt Stock and Debt Ceiling at the Aggregate Level

Note: The actual outstanding explicit local government debt at the aggregate level (solid line) is the end-of-year outstanding debt. The debt ceiling (blue dashed line) is the debt quota set by the State Council. The aggregate debt series before 2014 is obtained by aggregating province-level local government debt. The data source is the local government debt audit announcement. The debt series from 2014 to 2022 and the debt ceiling series are from the official website of the Ministry of Finance. The nominal GDP series is from the National Bureau of Statistics. Due to data availability, the debt series only starts in 2010. The grey shaded area indicates the periods when the debt quota management policy is implemented.

In a recent paper (Qu, et al. 2023), we empirically investigate how the ceiling on local government debt is allocated to prefectural cities in China after the debt management reform. Our empirical analysis indicates that the distribution of the debt ceilings depends on the bilateral interplay between local governments and their superior authorities. In particular, besides fundamental factors, political connections with provincial leaders and local application efforts induced by regional competition significantly raise the newly increased debt ceiling for prefectural cities. Here, we measure the extent of the application efforts by the growth gap between competitors. The underlying intuition is that a city with economic growth lagging behind its competitor has a stronger incentive to apply for larger debt quotas to stimulate its economy. According to purposes and repayment sources, local government debt in China can be classified into two types: general debt and special debt. General debt is used to finance public projects without return, including kindergartens, museums, etc.; while special debt is used to finance public investments with a certain capital return, including highways, railway stations, airports, etc. We find that the effects of local application are more pronounced for distributing the ceiling of special debt that is used to finance public projects with certain returns. We further evaluate the real consequences of the debt ceiling distribution. An increase in the debt ceiling (either on general bonds or on special bonds) leads to higher economic growth but dampens total factor productivity (TFP), and regions with tighter debt ceilings tend to obtain external finance by accumulating more implicit debt through LGFV.

Institutional Backgrounds

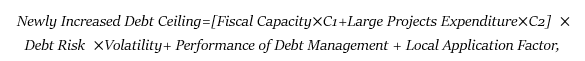

The distribution of debt ceilings follows a hierarchical procedure. The State Council first sets the ceiling of nationwide local government debt in the next year (debt stock in the last year plus newly issued debt), which is required to be approved by the National Congress. Then, the MoF allocates the debt ceiling to individual provinces based on the proposals put forth by provincial governments. In turn, the provincial department of finance allocates the assigned ceiling to prefectural-level cities, taking into account factors such as credit risks and economic conditions associated with each city. In March 2017, the MoF further issued a detailed measure of the ceiling allocation on newly issued local government debt. According to the official document, the newly increased debt ceiling should follow a general formula that takes the form of

where coefficients C1 and C2 are determined based on the fiscal capacity, large project expenditures, and scale of the annual nationwide increase in local government debt ceilings; Fiscal Capacity includes fiscal capacity for the general public budget and that for government managed funds. Volatility is a measure of the stability of local government debt growth, aiming to prevent excessive growth and abnormal fluctuations in outstanding debt. The interval of this parameter is determined by the average growth rate of new debt ceilings approved by the National People's Congress. Debt Risk reflects the borrowing capacity and debt repayment risk of local governments, which is computed by dividing the previous year's government debt ceiling by the standard limit. Furthermore, appropriate adjustments should be made to the respective regions based on the assessment of management performance.

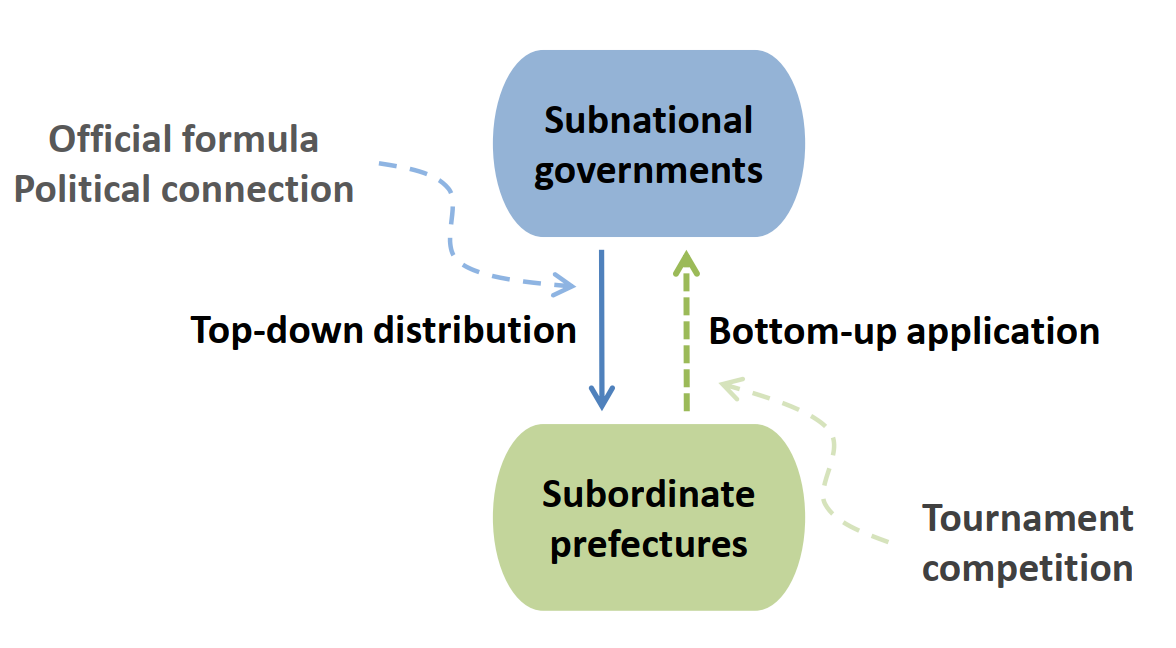

Regarding Local Application Factor, the official document does not provide a concrete definition. However, the newly increased ceiling is required not to exceed the amount requested by that particular region. This implies that Local Application Factor plays a crucial role in ceiling allocation. In China’s political institutions characterized by regional authoritarian and centralized political governance (Xu, 2011), political networks with superior government and local competition both play critical roles in shaping government actions. Thus, it is particularly worthwhile to examine the impact of strategic interactions between local and superior governments on the distribution of debt ceilings.Figure 2 intuitively presents the potential distribution mechanisms of local government debt ceilings in China.

Figure 2. The Distribution Mechanism of Local Government Debt Ceilings

Uncovering the distribution of debt ceilings

To facilitate further analysis, based on Qu et al. (2023), we construct a comprehensive and unique dataset that covers all the information about the outstanding debt, debt ceiling, and fiscal capacity of prefecture cities, as well as a biographical database for Chinese leaders. Next, based on the policy document issued by MoF, we construct corresponding variables to measure factors in the official formula that exhibit variations at the prefecture city level, including Fiscal Capacity (measured by the city’s total public budget), Large Project Expenditure (reflected by the city’s fixed capital investment and public budget), Debt Risk (measured by the ratio between the debt ceiling of a city and the standard debt ceiling, where the latter one is defined as the city’s public budget revenue multiplied by the country-average duration of debt maturity), and Performance of Debt Management (measured by the city’s debt-to-income ratio, and the percentage of the used ceiling in the previous year). To capture the bidirectional interaction between local and sub-national governments that may affect the Local Application Factor, we consider both the political connection with provincial officials and the extent of local application efforts (measured by the region’s growth gap between competitors).

To analyze the determinants of debt allocation, we regress the newly increased debt ceiling allocated to prefecture cities on the aforementioned indicators. For the explanatory variables, we first include the corresponding indicators from the official formula that exhibit variations across prefecture cities, including Fiscal Capacity, Large Project Expenditure, Debt Risk, and Performance of Debt Management. We include time and individual fixed effects to absorb other indicators without variations at the city level. After controlling for these observable factors, we further incorporate the variables for political connections and regional competition to estimate the impact of institutional factors on the ceiling distribution. Additionally, our econometric model accounts for a series of city-level economic variables, the personal characteristics of city leaders, and official turnovers.

Our baseline estimation shows that the coefficients of most observable factors in the official formula are significant, confirming the debt ceiling allocation formula specified by MoF. Moreover, the coefficient of political connection is significantly positive, implying that a city with an informal connection with the provincial government tends to acquire a higher debt ceiling. In addition, we find that the growth gap induces a significantly negative impact on the increase in the debt ceiling. This suggests that regions experiencing intense competition make greater efforts to apply for a higher debt ceiling in order to stimulate their local economies.

Heterogeneity analysis indicates that for a region with higher competitive intensity or more competitors, the local government has more incentive to apply for a higher debt ceiling when its economic performance falls behind. Moreover, political connection and regional competition exhibit significant effects for prefecture cities governed by young leaders while becoming insignificant for those governed by older leaders. This is because local leaders face a finite career horizon due to the mandatory retirement age of 60, and the likelihood of termination increases with age.

Different Types of Local Government Debt

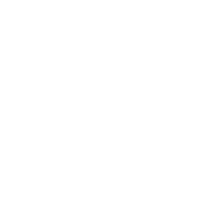

In recent years, the volume of newly issued special local government debt experienced a higher growth rate than that of general local government debt, as shown in the left panel of Figure 3. Moreover, the right panel of Figure 3 presents faster growth in the ratio of newly issued special debt to GDP, with the gap widened during the period of the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, we further explore the heterogeneity in the distribution mechanisms of these two types of debt. We find that the effects of local application induced by regional competition are more pronounced in the distribution of special debt ceilings. This finding aligns with the common observation that local governments tend to rely more on special debt to finance public projects.

Figure 3. Composition of Newly Issued Local Government Debt in China

Note: The left panel is the aggregate level of newly issued local government debt in nominal terms (trillion yuan). The right panel is the newly issued local government debt-to-GDP ratio. The data series is collected from China Electronic Local Government Bond Access (CELMA).

Real Consequences of Debt Allocation

Our estimation suggests that an increase in the debt ceiling raises local GDP growth but dampens TFP growth. This implies that loosening the debt ceiling could stimulate short-term GDP but may not necessarily contribute to productivity improvement. This finding aligns with the studies by Cong et al. (2019) and Huang et al. (2020), which show that local government debt may dampen allocation efficiency by crowding out private investment. Furthermore, we show that the newly increased debt ceiling has a negative relationship with the issuance of municipal bonds, indicating that cities with tighter debt ceilings are more inclined to resort to LGFV as an alternative financing channel. This may lead to potential risks due to the accumulation of implicit government debt.

Conclusions

We document the impact of bilateral interactions between local and their superior governments on the spatial distribution of public resources. Our study provides rich policy implications to understand intergovernmental interactions, as well as the unintended consequences of debt management policies. As shown in Song and Xiong (2024), tighter control of local government debt in post-2008 period would have been more critical to sustaining growth. Thus, policymakers need to take into account the bidirectional intergovernmental interactions when designing debt management policies or other centralized regulation reforms.

1 After the regulation policies starting since 2014, the central government further requires the local governments to replace all outstanding non-government-bond debt with local government bonds through a three-year debt-swap program. In the process of debt swap, debt issued by LGFVs is converted to local government bonds only if the debt is connected with local governments or the government claims the repayment obligation. Our paper focuses on the underlying mechanism that drives the dynamics of explicit debt, particularly after the policy reform.

References

Bai, Chong-En, Chang-Tai Hsieh, and Zheng Michael Song. 2016. “The long shadow of China’s fiscal expansion,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 2016 (2), 129–181.

Chen, Zhuo, Zhiguo He, and Chun Liu. 2020 “The financing of local government in China: Stimulus loan wanes and shadow banking waxes,” Journal of Financial Economics 137 (1), 42–71

Cong, Lin William, Haoyu Gao, Jacopo Ponticelli, and Xiaoguang Yang. 2019. “Credit allocation under economic stimulus: Evidence from China,” The Review of Financial Studies 32 (9), 3412–3460.

Huang, Yi, Marco Pagano, and Ugo Panizza. 2020. “Local crowding-out in China,” The Journal of Finance 75 (6), 2855–2898.

Qu, Xi, Zhiwei Xu, and Jinxiang Yu. 2023. "Debt Management and Strategic Interactions in Top-Down Bureaucracy: Evidence from China." SSRN Working Paper. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4622310

Qu, Xi, Zhiwei Xu, Jinxiang Yu, and Jun Zhu. 2023. “Understanding local government debt in China: A regional competition perspective,” Regional Science and Urban Economics 98, 103859.

Song, Zheng and Wei Xiong. “Risks in China’s financial system,” Annual Review of Financial Economics 10, 261–286.

Song, Z. and Xiong, W., 2023. The Mandarin model of growth, Working Paper.

Xu, Chenggang. 2011 “The fundamental institutions of China’s reforms and development,” Journal of Economic Literature 49 (4), 1076–1151

Zhang, Yuanyan Sophia, and Steven Barnett. 2014. “Fiscal vulnerabilities and risks from local government finance in China,” IMF working paper.

;

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email