Share Pledging in China: Funding Listed Firms or Funding Entrepreneurship?

Our recent study analyzes the use of share pledging funds in the context of China. Survey evidence shows that a majority of the largest shareholders (67.3%) used pledging funds outside their listed firms, including financing their entrepreneurial activities. Empirically there exists a positive and likely causal relation between shareholders’ pledging transactions and their entrepreneurial activities. Shareholders with better access to share pledging invest more heavily in industries with above-median growth potential.

Considering the financing flexibility embedded in the share pledging market, together with listed firms’ shareholders’ proven business acumen and strong social connections, our recent study (He, Liu, and Zhu 2022) explores the role of share pledging (as a financing vehicle) in promoting entrepreneurial activities in the context of China.

Significance of the Share Pledging Market

China’s share pledging system was established in the mid-1990s and has been well received by shareholders since then. The volume of newly pledged shares grew at an annual rate of 18.6% between 2007 and 2020. At the market’s peak in 2017, more than 95% of the A-share listed firms had at least one shareholder pledged, with the total value of pledged shares amounting to 6.15 trillion RMB (more than 10% of the total market capitalization).

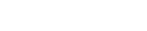

Before 2013, share pledging was solely organized in the over-the-counter (OTC) market, where commercial banks and trust firms are major lenders. In 2013, share pledging was introduced to the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges, with securities firms being the major lenders. This initiative greatly expedited the development of share pledging: after this policy shock, the annual transaction volume between 2013 and 2020 reached 204 billion shares (1,057 billion RMB), compared to 39 billion shares (192 billion RMB) per annum during 2007 and 2012.

Figure 1: Shares pledged in the Chinese market, 2007–2020. This figure plots the number of listed firms’ shares newly pledged by major shareholders who hold 5% of the total shares or more in each year from 2007 to 2020.

In late 2017, the authorities started to tighten regulations on share pledging, and the Chinese share pledging market gradually shrank. As shown in Figure 1, the annual growth rate of pledging volume was -18.9 % between 2018 and 2020.

Usages of Share Pledging Funds

We first infer the use of share pledging funds based on public disclosures on pledging transactions and related-party transactions between shareholders and their listed firms. In sharp contrast to common belief, during 2007 to 2019, only funds from 7.8% of share pledging transactions were used for the listed firms, while the remaining 92.2% were used to finance shareholders’ other activities.

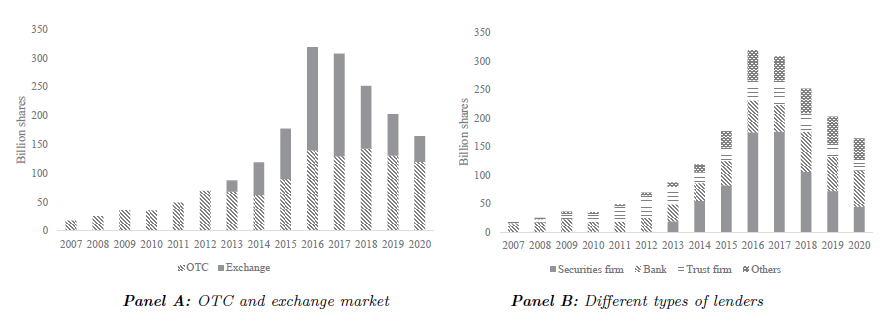

Figure 2: Survey results on use of share pledging funds. This figure plots the frequencies of use of share pledging proceeds based on the Tsinghua PBC School of Finance - China Securities Regulatory Commission 2019 survey.

We next break down how pledging funds are used outside the listed firms by taking advantage of a joint survey by Tsinghua PBCSF and the China Securities Regulatory Commission in 2019. We collected responses from 3,626 of the 3,628 Chinese public firms, representing a response rate of 99.99%. As Figure 2 shows, 60.1% of the responding firms reported that their largest shareholders had used share pledging in the past. Within those firms with pledging shareholders, 36.1% reported that their shareholders decided to support their listed firms with the proceeds. However, a larger fraction of them (67.3%) used the pledging funds outside the listed firms. Among them, their largest shareholders could repay personal debts (25.3%), spend for personal consumption (13.6%), and/or make financial investments (5.2%); but, most relevant to our study, 33.0% of them invested the funds outside the listed firms and established/invested in new firms.

This last point is the direct evidence that share pledging is not only a financing tool to support the listed firms, but also a potential source of financing for entrepreneurial activities. First, share pledging loans are less costly and more accessible to potential entrepreneurs. The interest rate is comparable to that of bank loans, ranging from 5% to 15%. Second, shareholders are able to use share pledging loans (and follow-on rollovers) to finance long-term entrepreneurial projects. Although a median pledging loan’s maturity was 1.0 year in our sample, it was rolled over for once by the shareholder and reached an effective maturity of 2.1 years. The 75th percentiles for the rollover number and the effective maturity were 5.0 times and 3.5 years, respectively.

Share Pledging and Entrepreneurship

We utilize the launch of the exchange market in 2013 as a quasi-natural experiment, and perform a difference-in-differences (DiD) analysis to establish the causal relation from share pledging to entrepreneurial activities. We posit that the launch generates significantly larger supply shocks on share pledging to natural person (individual) shareholders than to legal entity shareholders (companies or organizations that hold a listed firm’s shares), who are ultimately owned by natural persons. Typical legal entity shareholders in the Chinese stock market include companies, financial managers (e.g., mutual funds), and nonprofit organizations (e.g., university endowment funds).

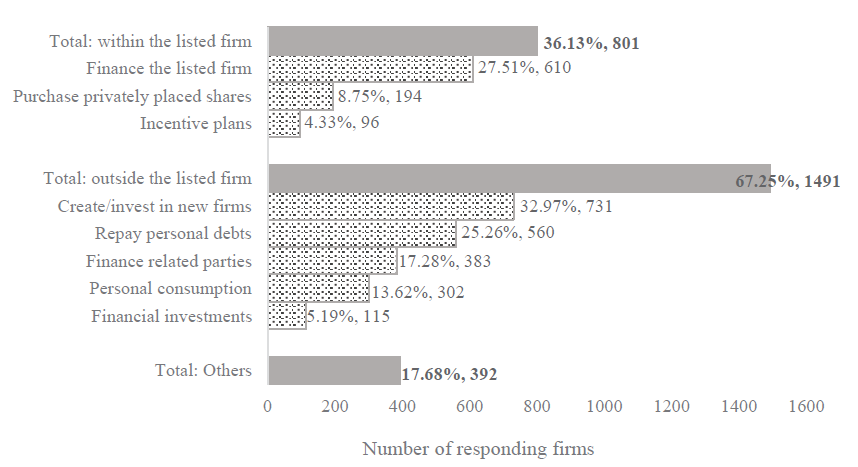

Figure 3: Share pledging and entrepreneurial activities around the 2013 reform. Panel A plots the average probability and loan amount of new share pledging in each year for natural person and legal entity shareholders. Panel B and C plot the average number of add-on firms (including new firms created by a shareholder and existing firms in which a shareholder makes her first investment) and new firms held by natural person and legal entity shareholders around the launch of the exchange market in 2013, respectively.

Before 2013, most share pledging loans were granted to legal entity shareholders; natural person shareholders were treated as retail customers by commercial banks in the OTC market and granted only small credit lines. Since 2013, loan supply to natural person shareholders—now by securities firms, as opposed to commercial banks—grew significantly in the exchange market; this is because 1) securities firms’ lending decisions depend on the quality of collateral rather than the shareholders’ identities; 2) securities firms are keen on promoting share pledging among natural person shareholders; and 3) securities firms make the pledging procedures more friendly to natural person shareholders. Therefore, relative to legal entity shareholders, natural person shareholders are more exposed to the positive supply shock caused by the launch of the exchange market.

Figure 3 shows, in the three years leading up to the 2013 reform, both pledging probabilities of natural person (the treated group) and legal entity (the control group) shareholders grew at a similar pace. However, after the reform shock, share pledging by natural person shareholders increased much more quickly and caught up with the level of legal entity shareholders in one year. The entrepreneurial activities (defined as creation of new firms and first investments in existing firms) by natural person and legal entity shareholders show similar patterns.

A formal DiD analysis suggests that after the launch of the exchange market, the increase in the number of add-on firms held by natural person shareholders exceeds that of legal entity shareholders by 113% of the national average, suggesting a causal relation between share pledging and entrepreneurial activities. This pattern is driven by treated shareholders’ creation of new firms: the increase in the number of new firms created by treated natural person shareholders exceeds that of legal entity shareholders by 144% of the national average, while the relative increase in existing firms is insignificant.

We also show that the “Mass Entrepreneurship and Innovation” policy and the new corporate law in 2014, which encouraged entrepreneurial activities by grassroots individuals and hit the bottom distribution in Chinese entrepreneurship, is unlikely to drive our DiD results. In our sample, the shock on entrepreneurship took shape starting in 2013, which was one or two years before these policies. More importantly, these policies target early-stage entrepreneurs, which do not overlap with those well-established major shareholders of listed firms we consider. In fact, during our sample period of 2010 to 2018, the median registered capital of firms created by listed firms’ natural person shareholders is 40 times that of all firms in the economy. The size distribution of firms created by shareholders around the policy shocks suggests that, after 2014, listed firms’ natural person shareholders create more larger firms than before (the fraction of firms with more than 20M RMB registered capital increases from 40.5% to 48.6%); in contrast, in the economy the creation of new firms mostly falls into the (501K,1M] and (1M,5M] buckets, with frequency increases of 10.2% and 5.3%, respectively. Importantly, there is no clear increase of new firm creation in these two buckets in our sample with listed firms’ natural person shareholders.

Furthermore, our findings on shareholders’ capital allocation are consistent with those on firm numbers. Shareholders with better access to share pledging invest more heavily in industries with above-median growth potential, and their new equity investments seem to be efficient.

(Zhiguo He, Booth School of Business, University of Chicago; Bibo Liu, PBC School of Finance, Tsinghua University; Feifei Zhu, School of Finance, Central University of Finance and Economics)

References

Brandt, Loren, and Hongbin Li. 2003. “Bank Discrimination in Transition Economies: Ideology, Information, or Incentives?” Journal of Comparative Economics 31 (3): 387–413. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0147-5967(03)00080-5.Meng, Qingbin, Xiaoran Ni, and Jinfan Zhang. 2019. “Share Pledging and Corporate Risk-Taking: Insights from the Chinese Stock Market.” Working paper. http://cfrc.pbcsf.tsinghua.edu.cn/Public/Uploads/upload/CFRC2019_1827.pdf.

Pang, Caiji, and Ying Wang. 2020. “Stock Pledge, Risk of Losing Control, and Corporate Innovation.” Journal of Corporate Finance 60, 1015–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2019.101534.

Cai, Hongbin, Yuyu Chen, and Li-An Zhou. 2010. “Income and Consumption Inequality in Urban China: 1992–2003,” Economic Development and Cultural Change 58 (3). https://doi.org/10.1086/650423.

Song, Zheng, Kjetil Storesletten, and Fabrizio Zilibotti. 2011. “Growing like China.” American Economic Review 101 (1), 196–233. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.101.1.196.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email