Misallocation, Selection, and Productivity: A Quantitative Analysis with Panel Data from China

We examine the distorting effects of China’s land institutions on aggregate agricultural productivity and other outcomes. We argue these distortions affect two key margins: (1) the allocation of resources across farmers (misallocation); and (2) the type of farmers who operate in agriculture (selection). Empirically, we find that selection significantly amplifies the costs of misallocation, suggesting important gains to policies that provide households more secure, transferable rights. Our use of household fixed effects estimates for both productivity and distortions address concerns of the effects of measurement error on estimates of misallocation.

China’s Land Institutions

The Household Responsibility System (HRS), established in rural China in the late 1970s and early 1980s, dismantled collective farming under Mao and extended use rights over farmland to rural households. These reforms triggered an initial spurt in productivity growth in agriculture in the early 1980s that subsequently dissipated (Lin, 1991).

Under the HRS, ownership of agricultural land remained vested with the village. Village officials administratively allocated use rights among rural households on a highly egalitarian basis that reflected household size. The law governing the HRS provided secure use rights over cultivated land for 15 years (in the late 1990s use rights were extended to 30 years); however, village officials often reallocated land among households before the 15-year period expired (Benjamin et. al., 2002). A primary motivation of the reallocations was to accommodate demographic changes within a village.

In the course of reallocations, village officials reallocated land from households with family members working off the farm to households solely engaged in agriculture. In principle, households had the right to transfer their use rights to other households; however, land rental markets were thin. The limited room for farm rental activity is frequently associated with perceived “use it or lose it" rules: households that did not use their land and either rented it to others or let it lie fallow risked losing the land during the next reallocation. The egalitarian allocation of land combined with implicit constraints on land rentals implies that better farmers were not able to increase their operational farm size. Over the period we analyze, average farm size remained constant.

Farm Productivity, Distortions, and Misallocation

If resources are allocated efficiently, marginal products are equalized across factors of production. Market distortions drive wedges between prices facing households and prevent the flow of resources to their highest valued use. A key and novel insight of our paper is that there is an important interaction between selection and misallocation. Selection can amplify the misallocation effect of distortionary policies through its effect on occupational choice and thus the distribution of productivity.

To examine the effect of China’s land policies, we draw on panel rural household survey data collected by the Research Center for Rural Economy under the Ministry of Agriculture in China for the period between 1993 and 2002. Altogether, we have data on more than 8,000 households drawn from 110 villages in 10 provinces of China; for approximately 6,000 of these households, we have data for all years the survey was carried out. The survey provides highly detailed information on household income, labor supply, and inputs and outputs in agriculture. The average number of households surveyed per year in a village is a quarter to a third of all households.

We use these data to estimate household total factor productivity (TFP) and total revenue productivity (TFPR), which is a measure of distortions facing individual households in land and capital markets. In the cross-section, these estimates may reflect measurement error, transitory input or output shocks, as well as unobserved village characteristics that can impact dispersion of productivity and the implied gains from reallocations. We leverage the panel dimensions of our data to net out these factors and obtain estimates of households’ permanent or fixed-effect levels of TFP and TFPR.

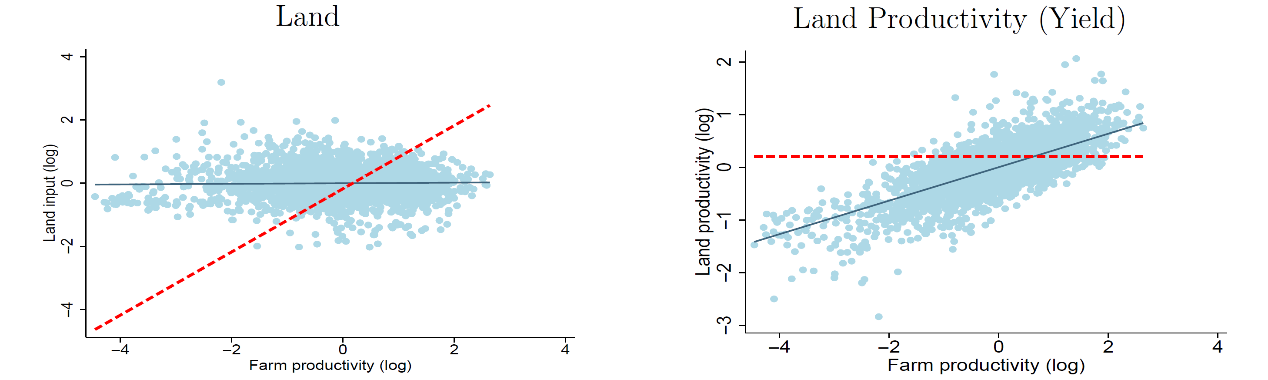

Figure 1 documents the allocation of land across farms by farm productivity (in logs) using our baseline fixed effect estimates of TFP. Land use is not systematically positively correlated with farm productivity across farms. This pattern is inconsistent with an efficient allocation of resources across farmers in China (red dotted line). It is however consistent with the institutional setting in China, most notably, the fairly uniform administrative allocation of land among households within a village that prevents the flow of resources to the farmers who are most productive.

Figure 1: Land Allocation by Farm Productivity

In Figure 2, we plot farm-idiosyncratic distortions as captured by TFPR against farm TFP (in logs) for our baseline fixed effects measures. We observe a strong correlation between farm distortions and TFP, with a correlation of 0.91. The more productive farmers face larger distortions. This implies that the farmers hurt most from the institutional setting in China are the more productive ones who would have expanded their farming operations the most in unfettered markets.

Figure 2: Farm-Specific Distortions and Productivity

How much larger would aggregate output (and as a result, TFP) be in agriculture if farm-specific distortions were eliminated holding constant aggregate resources? Table 1 reports the efficiency gains from factor reallocation using our baseline fixed effect estimates of farm productivity. Eliminating misallocation across household farms within villages in China increases TFP and agricultural output by 24.4 percent (first row, column one). This misallocation occurs across households that differ in their productivity (correlated) as well as among households with similar levels of productivity (uncorrelated). We find that sixty percent (13.9/24.4) of the reallocation gains are due to reallocating resources across households that differ in their productivity. Using more conventional cross-sectional measures of farm TFP and distortions typically used in the literature, average reallocation gains are 54 percent within villages and 83 percent allowing for across-village allocation, suggesting these measures may overestimate reallocation gains.

Misallocation and Selection Across Sectors

Market frictions not only contribute to misallocation but may also distort occupational choice between working in agriculture and non-agriculture. Selection can amplify the misallocation effect of distorting policies and influence the extent of measured misallocation through its effect on the distribution of productivity. Intuitively, institutions generating misallocation may have a particularly negative effect on farmers who are more able , who are then less likely to farm, further reducing average agricultural labor productivity.

To examine these possibilities, we develop and estimate a two-sector general equilibrium Roy model of occupational choice that leverages our measures of idiosyncratic distortions and TFP across farmers and panel household information on incomes in agriculture and non-agriculture. Details are provided in the paper.

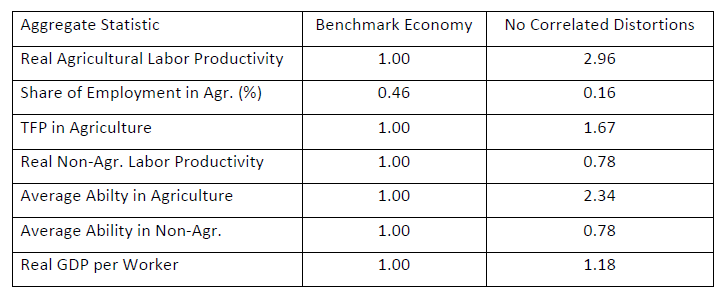

Table 1: The Effects of Correlated Distortions

“No Correlated Distortions” eliminates the component of farm-level distortions associated with agricultural ability. Aggregate variables, except for the share of employment in agriculture, are reported relative to values in the benchmark economy.

Table 1 reports the effects of a counterfactual exercise that assesses the effects of China’s land institutions by eliminating the distortions that are correlated with agricultural ability. Note that in this experiment there is still misallocation associated with dispersion of distortions unrelated to farm productivity. Eliminating these “correlated” distortions within villages, labor productivity in agriculture rises by almost threefold, a product of an increase in agricultural TFP of 67 percent and a reduction in the share of the labor force in farming from 46 percent to only 16 percent.

The increase in agricultural TFP can be attributed to a reduction in misallocation across farms and to incentives for higher-ability farmers to work in agriculture with the removal of the constraints on farm size. Improvements in productivity through these two channels reduce the share of employment in agriculture, which further raises agricultural labor productivity by increasing the amount of inputs per farmer.

In contrast, average ability, and hence real labor productivity in non-agriculture falls with the reallocation of workers to the non-agricultural sector, not all of whom are as productive in that sector. Despite the significant impact on labor productivity in agriculture, real GDP per worker increases a much more modest 18 percent. This reflects the dampened effect on aggregate output associated with the large shift of labor to a sector that experiences a fall in productivity relative to the benchmark. Nonetheless, these gains remain sizable relative to real GDP growth in most developing countries.

Conclusion

We analyze the costs of China’s land institutions through the early 2000s, highlighting the important amplification effects through selection. These same institutions were also seen as vital to social security and equity considerations, a dimension we abstract from in this paper. The implementation of the Land Management Law (LML) in 1998 and the Rural Land Contracting Law (RCLC) in 2003 helped address some of the land security issues by restricting village reallocations (see Note 1). More recently, pilot experiments have been carried out in several major Chinese cities that have further expanded household land rights. Examining the implications of these reforms for both growth and equity is important. Consolidations of farm operations, enabled through these reforms, could improve not only the allocation of resources and selection but also incentivize mechanization and other productivity enhancing investments. Finally, more-secure property rights can lead to better allocations across sectors and space, as we explore in new work.

Note 1: Chari et. al. (2021) provide an assessment of these reforms on land rental and productivity.

References

Adamopouos, T, Brandt, L., Leight, J., and Restuccia, D. Forthcoming. Misallocation,

Selection and Productivity. A Quantitative Analysis with Panel Data. Econometrica.

Adamopouos, T, Brandt, L., Chen. C., Restuccia, D. and Wei, X. (2021). Land Security and Mobility Frictions. Working paper.

Benjamin, D. and Brandt. L. (2002). Property Rights, Labor Markets, and Efficiency in a Transition Economy. The Case of Rural China. 35.4. Canadian Journal of Economics. 689–716.

Chari, A. Liu. E., Wang, S., and Wang, Y. (2021). Property Rights, Land Misallocation, and Agricultural Efficiency in China. Review of Economic Studies. 88.4: 1831–1862.

Lin, J. Y. (1992). Rural Reforms and Agricultural Growth in China. American Economic Review. 82.1. 34–51.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email