From Rural Schools to City Factories: Assessing the Quality of Chinese Rural Schools

Rural school quality is low and varies significantly across provinces. We estimate provincial variations in school quality from the labor market returns to years of schooling of interprovincial rural migrants educated in different home provinces but working in the same urban labor market. School quality is higher and provincial variation is lower for younger cohorts, indicating at least partial effectiveness of recent policies aimed at improving the quality of rural schools.

Improving labor productivity in China has been closely related to internal rural-to-urban migration (Tombe and Zhu 2019), thus linking economic performance to the quality of education in rural areas. We connect this observation to the extensive research on the long-term importance of human capital for both individual labor market earnings and overall economic growth in China (Hanushek and Kimko 2000; Hanushek and Woessmann 2012; Hanushek et al. 2025). Understanding the human capital level of migrant workers and how their human capital is shaped by various factors, most importantly the school education they have received, is of vital importance for designing policies that promote sustained future growth.

We determine the human capital level of migrant workers from estimates of the labor market rate of return to their years of schooling (Card and Krueger 1992). Due to hukou restrictions, migrant workers generally attend school in their rural hometowns, where their hukou is registered. China’s tremendous regional disparity in economic development level and public education quality shows up in the rates of return to schooling for migrant workers’ hukou province.

We use data from the China Migrants Dynamic Survey (CMDS) and focus on interprovincial rural migrants who have completed only basic education (i.e., primary through high school). These sampling choices permit us to separate the school quality of the hukou province from the demand side of local labor markets, because we have quite precise knowledge of where each migrant was educated. Conceptually, for an individual urban labor market (where demand factors are constant), we relate observed variations in rates of return to schooling to the province of the migrants’ schooling. Empirically, we pool all migrants to estimate returns specific to each home province in models that include city-by-year fixed effects for each labor market where migrants are employed. We interpret the relative return to a year of schooling for each of the rural migrants’ home provinces as reflecting the educational quality of the home province. The focus on migrants does, however, require controlling for other, nonhuman capital influences on observed earnings: the percentage of adults with a college degree or above from each hukou province and variables that may affect both the pattern of migration decisions and labor market outcomes.

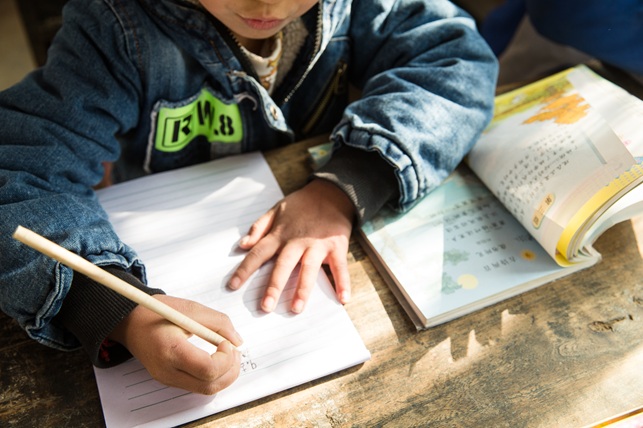

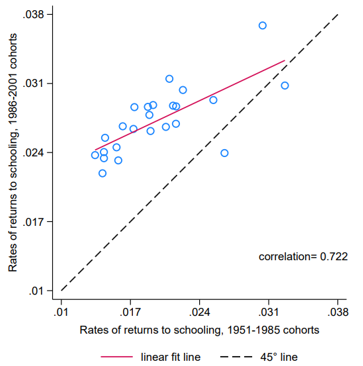

We have three main findings. First, Mincer returns to hukou province basic education for interprovincial migrants range from 1.6 to 3.1 percent for each additional year of schooling (Figure 1). These estimates are noticeably lower than those found for the urban-educated population and for samples including individuals with college education (Zhang et al. 2005), but they are higher than those for rural nonmigrants (De Brauw and Rozelle 2008). Second, controlling for observable factors potentially related to selectivity of migration decisions such as geographic distance of migration, differences in regional development level, and social networks, we estimate that the returns to schooling are significantly higher when migrants work in economically more developed cities than when they work in economically less developed cities (Figure 2). The returns in different types of cities of migrants from the same hukou provinces are highly correlated (greater than 0.7), suggesting fundamental differences in schooling quality by hukou provinces. Third, the returns to schooling are higher for the younger cohort (born between 1986 and 2001) than for the older cohort (born between 1951 and 1985) in all but two hukou provinces (Figure 3). Importantly, the cross-province variation in the returns is smaller for the younger cohort. While the returns for the two cohorts are highly correlated at 0.72, the coefficient of variation of 0.26 for the older cohort falls to 0.12 for the younger. These estimates indicate improved quality of basic education in all provinces and a convergence of basic education quality across provinces.

Figure 1. Rates of Returns to Schooling of 24 Major Hukou Provinces

Figure 2. Rates of Returns to Schooling for Migrants Working in Cities of Different Development Levels

Figure 3. Rates of Returns to Schooling for 1951-1985 and 1986-2001 Cohorts

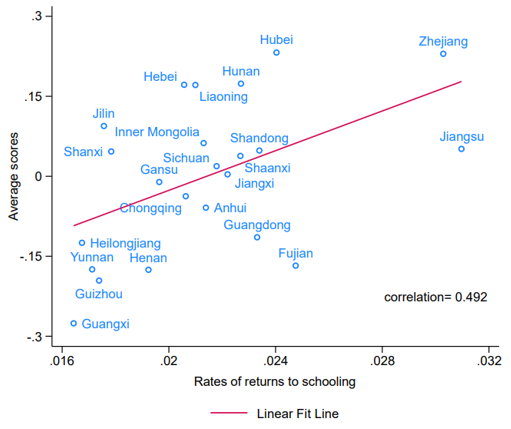

The returns are highly correlated (0.49) with cognitive skill test scores calculated for rural residents of the same age group from the 2014 China Family Panel Studies (Figure 4), suggesting a close association between the returns and the human capital level. We relate the provincial rates of return to provincial inputs for rural schools during the time when the migrant workers of the younger cohort attended school. Returns are associated with items that may characterize aspects of the province’s historic support for schools, such as the number of books per student or the area of school buildings per student, but are not associated with current school spending measures.

Figure 4. Rates of Returns to Schooling and Cognitive Test Scores

There are two important considerations for future study. First, rates of return to schooling in China vary by education level, by where one is schooled (urban vs. rural, different provinces), and by when one is schooled. Considering only one group out of the larger population provides an incomplete picture of the skills of the Chinese population. Second, the central government’s continued efforts to improve rural schools, including earmarked intergovernmental transfers, have improved the overall quality of rural schools and narrowed the gaps in rural school quality across provinces. However, we need a better understanding of how to raise the efficacy of school inputs to further improve rural school quality.

References

Card, David, and Alan B. Krueger. 1992. “Does School Quality Matter? Returns to Education and the Characteristics of Public Schools in the United States.” Journal of Political Economy 100 (1): 1–40. https://doi.org/10.1086/261805.

De Brauw, Alan, and Scott Rozelle. 2008. “Reconciling the Returns to Education in Off‐Farm Wage Employment in Rural China.” Review of Development Economics 12 (1): 57–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9361.2007.00376.x.

Hanushek, Eric A., Le Kang, Xueying Li, and Lei Zhang. 2025. “From Rural Schools to City Factories: Assessing the Quality of Chinese Rural Schools.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 34005. https://www.nber.org/papers/w34005.

Hanushek, Eric A., and Dennis D. Kimko. 2000. “Schooling, Labor-Force Quality, and the Growth of Nations.” American Economic Review 90 (5): 1184–1208. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.90.5.1184.

Hanushek, Eric A., Yuan Wang, and Lei Zhang. 2025. “Understanding Trends in Chinese Skill Premiums, 2007–2018.” Journal of Comparative Economics 53 (2): 584–608. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jce.2025.04.001.

Hanushek, Eric A., and Ludger Woessmann. 2012. “Do Better Schools Lead to More Growth? Cognitive Skills, Economic Outcomes, and Causation.” Journal of Economic Growth 17: 267–321. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10887-012-9081-x.

Tombe, Trevor, and Xiaodong Zhu. 2019. “Trade, Migration, and Productivity: A Quantitative Analysis of China.” American Economic Review 109 (5): 1843–72. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20150811.

Zhang, Junsen, Yaohui Zhao, Albert Park, and Xiaoqing Song. 2005. “Economic Returns to Schooling in Urban China, 1988 to 2001." Journal of Comparative Economics 33 (4): 730–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jce.2005.05.008.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email