Learning by Trading: How Reforming Trade Policy Boosted Firm Productivity in China

In China, granting firms the right to trade internationally boosted productivity, with gains growing over time and shared with workers through higher wages.

Whether exporting and importing make firms more productive – or whether only the most productive firms self-select into trade – has long shaped policy debates on trade and industrial development (Atkin et al. 2025). Experimental research in some contexts finds that granting export access can boost productivity (Atkin et al. 2017), but economy-wide analyses often face challenges due to selection bias. China’s ‘trading rights’ system created a clean, real-world test, allowing us to estimate the gains from trade and establish the mechanism behind these gains.

We study a trade regulatory policy adopted in China in the early 2000s that allowed only firms above a minimum registered capital level to participate in international trade. Firms ‘bunched’ just above this threshold qualified for trading rights, which subsequently raised their likelihood of trading and increased productivity over time. We show that the gains were driven by ‘learning by trading’ and find no evidence that these gains were achieved via R&D, product rationalisation, or higher mark-ups. Workers also share these gains via higher wages, with younger firms experiencing larger benefits.

Assessing China’s trade regulatory policy

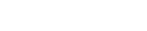

In the early 2000s, domestic-owned firms could only trade directly if their registered capital exceeded an official cut-off (RMB 3 million for most firms in East China in 2002). These firms responded by increasing their reported registered capital to just above the line, creating bunching in the density distribution at the cut-off (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Firms bunch at the registered-capital cut-off to obtain trading rights

Note: Figure 1 presents the observed (solid line) and the counterfactual (dashed line) distribution of registered capital, after controlling for rounding. There is excess bunching at the cut-off.

To study the impact of this policy, we combine three datasets: Chinese customs transactions (2000–2006), the annual survey of industrial firms (1998–2007) covering balance sheets and output, and product-level production data (2000–2006). We focus on East China in 2002 (the cleanest year, without mid-year changes) and use unaffected groups – foreign-invested firms (who had full rights regardless of registered capital) and pre-policy years – as placebo comparisons (Li, Lu, and Wang 2025). Our main outcome of interest is quantity-based total factor productivity.

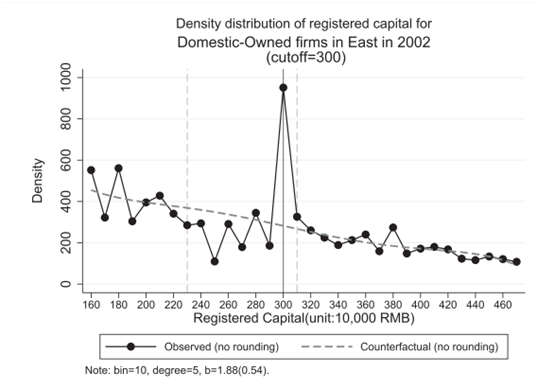

The bunching behaviour of firms allows us to identify the causal impacts. The idea is intuitive: given that some firms moved from below to above the threshold – leading to changes in the conditional outcome mean distribution around the cut-off (Figure 2) – we can recover their average treated (with trading rights) and counterfactual outcomes (without trading rights), the difference of which identifies the causal impact.

Figure 2. Firms’ conditional outcome mean change at the cut-off due to bunching

Note: Figure 2 plots the conditional outcome mean at each registered capital bin. Compared to pre-policy (2000), the distributions post 2002 show jumps in trade participation and productivity at the cut-off, signalling that clearing up the threshold for trading rights impacted firm performance.

What changes when firms gain trading rights?

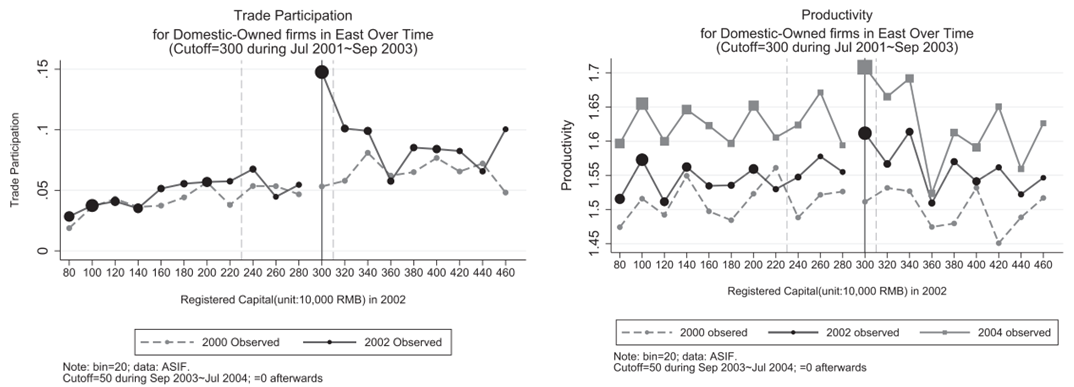

Two first-order outcomes move in the expected direction: among firms that bunch at the threshold, trade participation rises by 14.4 percentage points, and productivity rises by around 9.9% for these firms in the year they gain rights. These are intent-to-treat effects. Scaling by the change in trade participation implies a large productivity gain for firms that actually start trading.

The estimates pass several credibility checks. We see no jump either at the same threshold for domestic firms in a pre-policy year or for foreign-invested firms (who already had full trading rights regardless of capital). We also show that the observed pile-up at the threshold is not an artefact of round-number reporting.

Figure 3. Impact of obtaining trading rights on bunching firms’ performance

Note: Figure 3 plots the treated and counterfactual outcome for the bunching firms, where the solid and dashed lines denote the corresponding mean values. Obtaining trading rights increased trade participation and productivity for these bunching firms.

Gains build over time – consistent with learning by trading

The productivity effect grows over subsequent years and stabilises after the policy is removed. This dynamic pattern is hard to reconcile with pure selection or a one-off move along a fixed production frontier. Instead, it fits a learning-by-trading story: firms improve their processes, quality control, and knowledge as they engage in international markets, and these improvements take time.

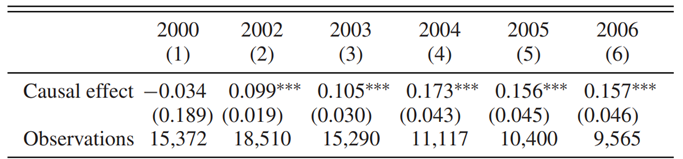

Table 1. Potential mechanism: Learning by exporting

Note: Table 1 reports the dynamic impacts of obtaining trading rights on bunching firms’ productivity. There was no impact in the pre-policy period (2000), but there was an increasing impact over time (in the post-policy period from 2002 to 2004), which gradually decreased when the threshold was removed afterwards.

Importantly, we do not find evidence that the gains are driven by increased R&D investment, product rationalisation (dropping or adding products), and/or higher mark-ups. The absence of these responses in the data steers us towards learning by trading as the main channel in this setting.

In addition, younger firms benefit more, consistent with greater scope to learn and fewer organisational frictions. Workers share in the gains through higher wages, indicating within-firm efficiency improvements.

Implications for trade policy

Our findings suggest the following policy implications:

- Administrative barriers matter. Simple eligibility rules can meaningfully constrain firms’ access to global markets. Lowering or removing such barriers can raise productivity.

- Expect learning to take time. Complementary policies, such as export promotion services, standards support, and buyer-seller matchmaking, can help firms climb the learning curve faster and spread benefits beyond early adopters.

- Targeting can amplify impact. Younger firms appear especially responsive; directing export-support resources to these firms may yield the highest returns.

Our findings align with experimental evidence that trade access can boost firm performance, while leveraging a national, multi-sector setting with clear policy-driven variation. By using bunching at a policy threshold – an identification strategy widely used in public finance – we provide credible, large-scale evidence that participating in international trade raises productivity and that these gains build over time. Developing countries can promote access to global markets to facilitate learning.

(This is reposted from an article originally posted at VoxDev.)

References

Atkin, D, A Khandelwal, L Boudreau, R Dix-Carneiro, I Manelici, P Medina, B McCaig, A Morjaria, L Pascali, H Pellegrina, B Rijkers, and M Startz (2025), “International trade,” VoxDevLit, 4(2).

Atkin, D, A K Khandelwal, and A Osman (2017), “Exporting and firm performance: Evidence from a randomized experiment,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 132: 551–615.

Li, Y, Y Lu, and J Wang (2025), “Productivity gains from trade: Bunching estimates from trading rights in China,” Review of Economics and Statistics, 107: 1275–1290.

Li, Y, Y Lu, and J Wang (2025), “Learning by trading: How reforming trade policy boosted firm productivity in China.” VoxDev, 11 Nov. 2026, https://voxdev.org/topic/trade/learning-trading-how-reforming-trade-policy-boosted-firm-productivity-china

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email