Why Are So Many Young Women Moving to China’s Big Cities?

It’s not just about jobs. It’s also about love, status, and the marriage market.

We document that migrant women have outnumbered migrant men in the 16–25 age bracket in Chinese cities. The gender imbalance has been more pronounced in larger cities. We use the gradual rollout of special economic zones across China as a quasi-experiment to establish the causal impact of urbanization on gender-differentiated incentives to migrate. We highlight the role of the marriage market: moving to cities increases rural women’s chance of marrying and marrying up.

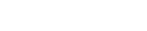

China’s cities are swelling with young people chasing opportunities. Look closer, and you’ll spot something striking: there is gender imbalance among young cohorts, largely driven by migration. Using information from China’s 2000 Population Census, Figure 1 shows a large surplus of females among migrants aged 16–25, defined as individuals who moved across counties. However, locals show a relatively balanced gender ratio.

Figure 1. Gender disparity by age for migrants and locals in China in 2000

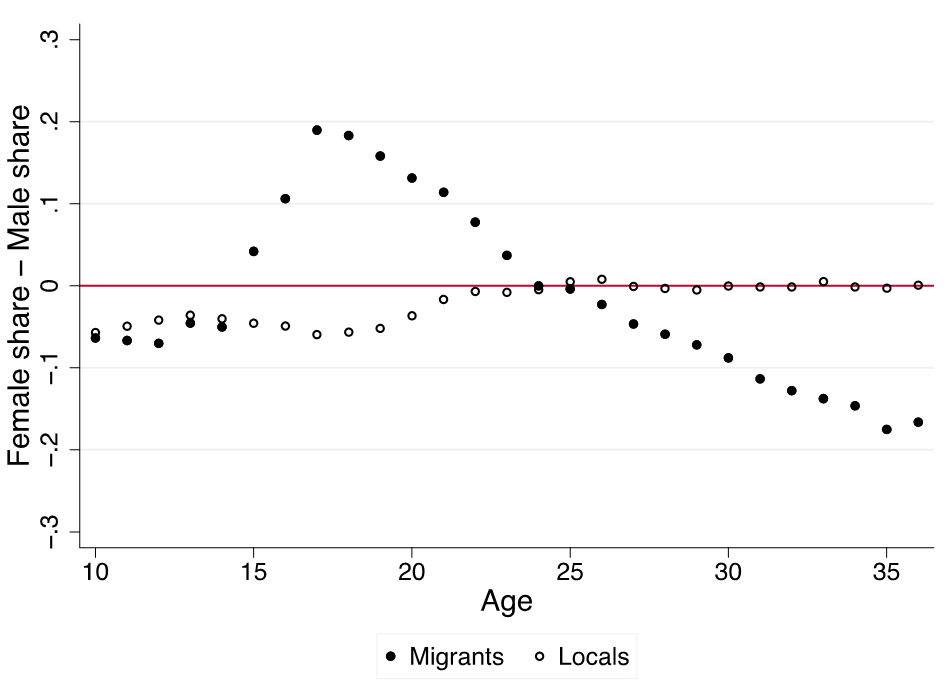

This pattern is not confined to a single city in China; it is observed nationwide. Panels (a) and (b) in Figure 2 show that the surplus of young females among migrants is more prominent in larger destinations. As a result, the overall gender imbalance among young individuals tends to increase with city size, as shown in panel (c). This pattern persists even after controlling industry fixed effects, as shown in panel (d).

Figure 2. Female share among young migrants across city size in China in 2000

The trend is not unique to China; comparable patterns have been documented in Vietnam, Latin America, and Europe (Tacoli 2012, Wiest et al. 2013, Pettay et al. 2021, Nguyen 2025).

What explains China’s version of this global phenomenon?

The marriage market effect: When romance meets urban economics

Our study (Koh et al. 2025) shows a surprising force at the center of the story: marriage markets.

Two deeply rooted social norms make urban China especially attractive for young women:

1. Status hypergamy – women are expected to “marry up.”

2. Patrilocality – after marriage, couples typically live near the husband’s family.

Taken together, these factors create a powerful incentive: women seeking access to a larger pool of higher-status men tend to migrate to cities prior to marriage. Evidence from China’s 2000 Population Census supports this pattern: among 257,484 migrants aged 16–25 in 1996–2000, “migrate to marry” was the second-most stated reason for moving among women, but close to irrelevant for men.

Thus, the narrative is not simply that “women move for jobs,” but rather that “women move for both employment opportunities and potential marriage prospects.”

A quasi-natural experiment: China’s special economic zones

To establish causation, we used the staggered rollout of special economic zones (SEZs) in the late 1990s. SEZs triggered sudden urban growth—but not because of gender-specific migration trends, making them ideal for causal identification.

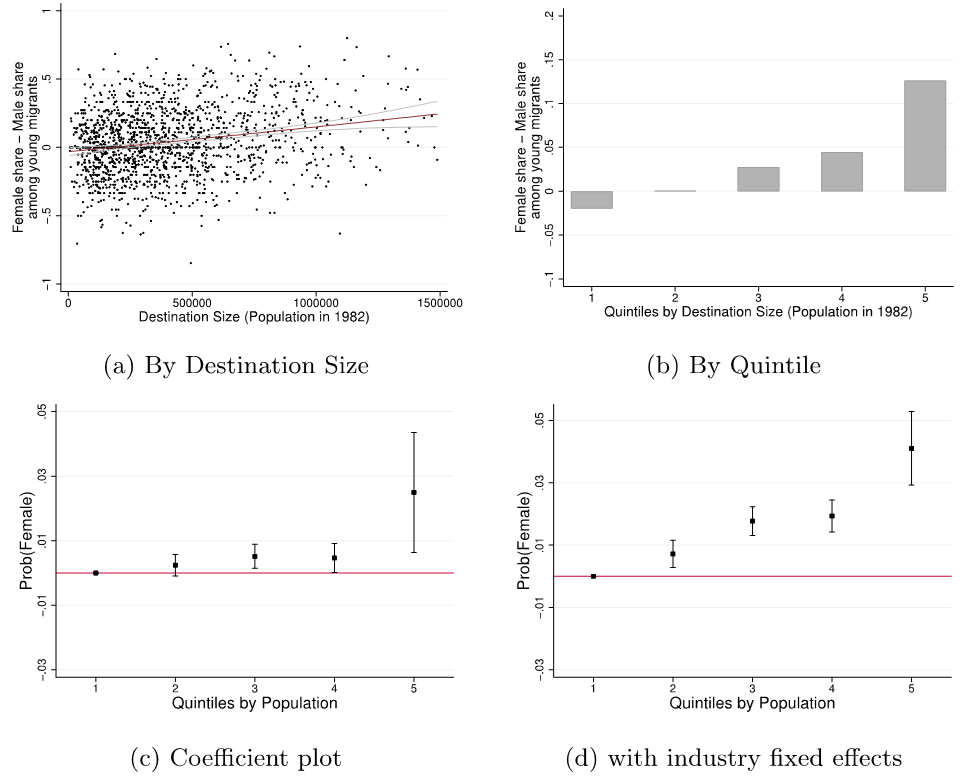

We estimate a staggered difference-in-differences model that uses not-yet-treated counties as the control group and defines treatment cohorts based on the year of SEZ opening. Figure 3 presents the dynamic average treatment effects on the treated. The top panel shows that SEZ openings led to a significant increase in migration among young individuals aged 16–25. The bottom panel further indicates that the female share of these young migrants rose by approximately 6 percentage points following the SEZ establishment.

We then extend the analysis to the individual level using a long-difference specification. More specifically, we examine whether people were more likely to migrate between 1996 and 2000 in response to SEZ shocks in potential destination counties. To capture these external incentives, we construct a “pull factor,” a composite measure of SEZ shocks realized during this period in potential destinations, weighted by predetermined migration networks. The results suggest that a one–standard deviation increase in the pull factor raises the probability of emigration from the origin county by 1.9 percentage points for young males and 2.1 percentage points for young females. The 0.2 percentage point difference (or 10% difference) may seem small, but given China’s population base, the scale of gender difference is huge and can be a major social issue.

Figure 3. Time-varying effects of SEZ establishment on young migrants

Among the various potential mechanisms, our empirical evidence points to marital incentives as an important channel. Subgroup analysis at the individual level reveals that responsiveness to the pull factor is substantially stronger for unmarried young females than for their male counterparts, whereas this gender asymmetry disappears among the married cohort.

We further replicate the analysis using a sample of ethnic minority groups—specifically Uyghurs, Tibetans, and Kazakhs—who are characterized by high rates of endogamous marriage. In this case, neither females nor males exhibit a statistically significant migration response to the pull factor, consistent with the notion that external attraction forces play a limited role in shaping their marital prospects.

What about jobs, schools, safety, or amenities?

We also explore alternative mechanisms. First, we examine whether SEZs might have altered local industrial structures in ways that disproportionately increased demand for young female workers. To test this, we control for gender-specific labor market changes into our estimation but find that young females remain more responsive to the pull force than their male counterparts. This suggests that labor market shifts are unlikely to be the sole channel.

Another possibility is that young females place greater value on educational opportunities or perceive a larger gender gap in the returns to education in cities, both of which could contribute to the surplus of young women in urban areas. However, when we reestimate our model excluding individuals who report education-related reasons for migration, our results remain largely unchanged.

Finally, young females may be more attracted to urban amenities. Since high-skilled individuals are generally more responsive to local amenities than low-skilled individuals (Diamond 2016), we check whether high-skilled workers are more sensitive to the pull factor. We find no evidence to support this channel.

Why this matters: From “leftover men” to policy design

The feminization of migration reshapes everything from labor markets to family structures:

· Rural areas lose young women and see rising “marriage market pressure” on men.

· This could deepen inequality between urban and rural regions.

· Policymakers will have to plan for more female-driven demand for housing, child care, health care, and safety services

In short: this isn’t just a story about where people work—it’s also about how and where people form families.

Global lesson: Urbanization changes gender norms

China isn’t unique. Studies show similar female-tilted migration in Latin America, Southeast Asia, and Europe. Wherever cities offer both economic opportunity and better marriage prospects, women lead the migration wave.

SEZs and other urban growth poles attract more than factories and capital—they draw future brides. In this sense, urban policy is inseparable from family policy.

Reference

Diamond, Rebecca. 2016. “The Determinants and Welfare Implications of US Workers’ Diverging Location Choices by Skill: 1980–2000.” American Economic Review 106 (3): 479–524. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20131706.

Koh, Yumi, Jing Li, Yifan Wu, Junjian Yi, and Hanzhe Zhang. 2025. “Young Women in Cities: Urbanization and Gender-Biased Migration.” Journal of Development Economics 172: 103378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2024.103378.

Nguyen, Minh-Ngoc, 2022. Population Sex Ratio in Urban and Rural Area in Vietnam from 2010 to 2023. Statista. (https://www.statista.com/statistics/1188382/vietnam-urban-and-rural-population-sex-ratio, published August 8, 2025).

Pettay, Jenni E., Virpi Lummaa, Robert Lynch, and John Loehr. 2021. Female-Biased Sex Ratios in Urban Centers Create a “Fertility Trap” in Post-War Finland. 32(4): 590-598.

Tacoli, Cecilia. 2012. Urbanization, gender and urban poverty: paid work and unpaid carework in the city.

Wiest, Karin, Tim Leibert, Mats Johansson, Daniel Rauhut, Jouni Ponnikas, Judit Timar, Garbor Velkey, and Ildiko Gyorffy. Selective Migration and Unbalanced Sex Ratio in Rural Regions. https://sisu.ut.ee/wp-content/uploads/sites/169/01_fr-semigra_main-report-and-scientific-report.pdf

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email