Digital Dividends? Rural E-Commerce and the Urban-Rural Income Gap

We examine the impact of China’s Rural E-Commerce Comprehensive Demonstration (RECD) project on the urban-rural income gap. Using county-level data from 2006 to 2022 and a time-varying difference-in-differences design, we find that participation in the RECD project led to a significant reduction in urban-rural income disparity. The effects were especially pronounced in less-developed regions, poverty-designated counties, and areas with weaker digital infrastructure and gains were disproportionately concentrated among rural households. These “biased” digital dividends contrast with market-driven e-commerce development, such as Taobao Villages, which tended to exacerbate inequality.

China’s rapid economic growth has been shadowed by a persistent urban-rural divide. The average disposable income of urban residents is still more than twice that of rural residents, a structural imbalance that challenges the country’s pursuit of “common prosperity.” As digital technologies reshape economies worldwide, a central question arises: can the spread of rural e-commerce (REC) reduce inequality, or does it risk amplifying the advantages of already better-connected regions?

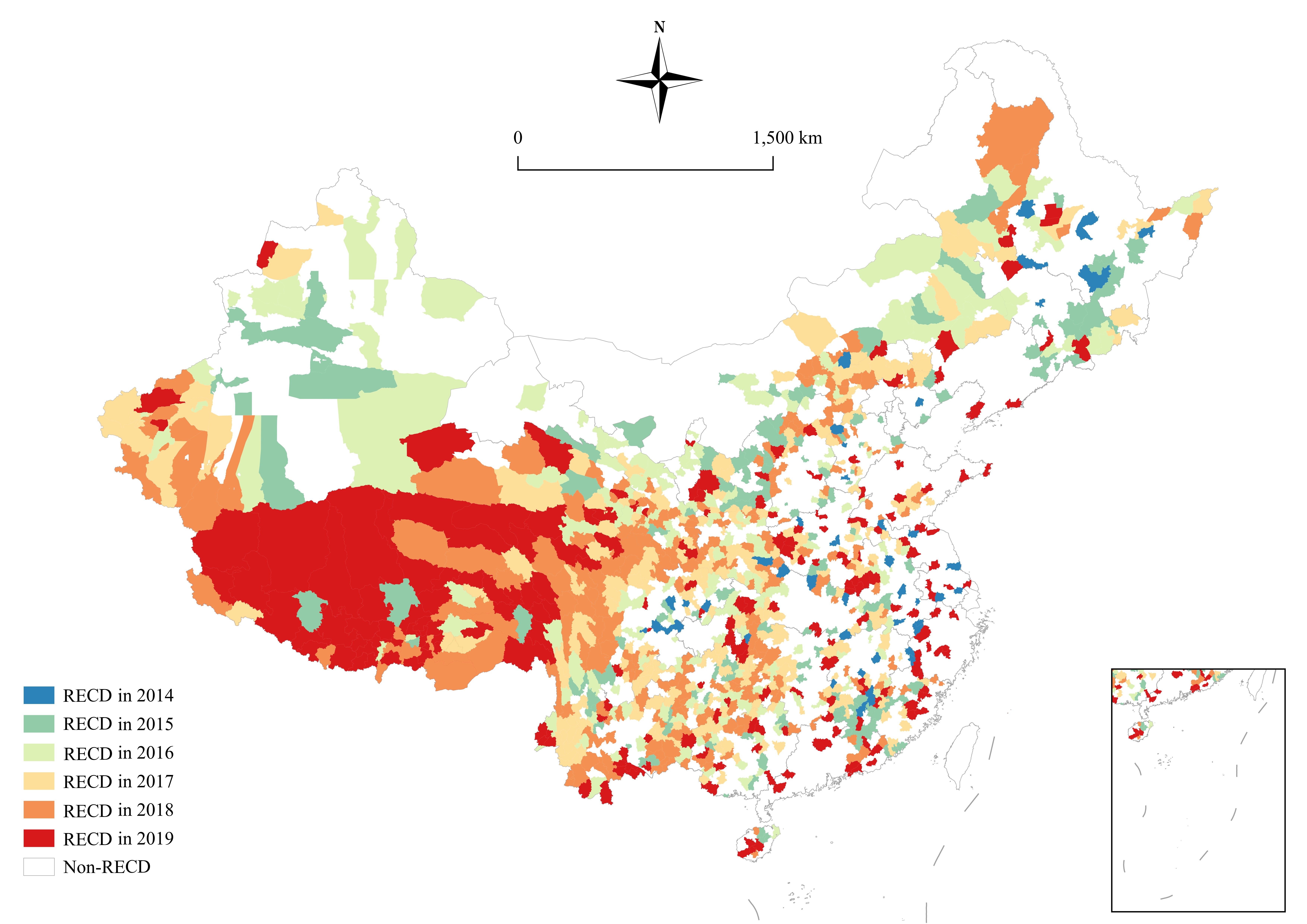

Figure 1. Spatial distribution of RECD pilot counties

Notes: This map shows the counties selected for the Rural E-Commerce Comprehensive Demonstration (RECD) project. Pilot counties are disproportionately concentrated in China’s less-developed central and western regions, in contrast to the peri-urban clustering of market-driven Taobao Villages.

Some evidence points to the latter. Studies of so-called Taobao Villages (TBVs)—grassroots clusters of e-commerce activity—suggest that while they have boosted local incomes, their benefits are concentrated in peri-urban areas with stronger industrial bases. Because TBVs often emerge from the relocation of urban industries, they can reinforce disparities rather than reduce them (Tang and Zhu, 2020; Liu and Zhou, 2023). These experiences echo a broader concern highlighted in the digital divide literature: new technologies often generate uneven benefits that favor better-endowed regions and early adopters (Juhász, 2018). This has fueled a policy debate: should REC be left to evolve organically, or does it require government guidance to ensure its benefits reach disadvantaged areas?

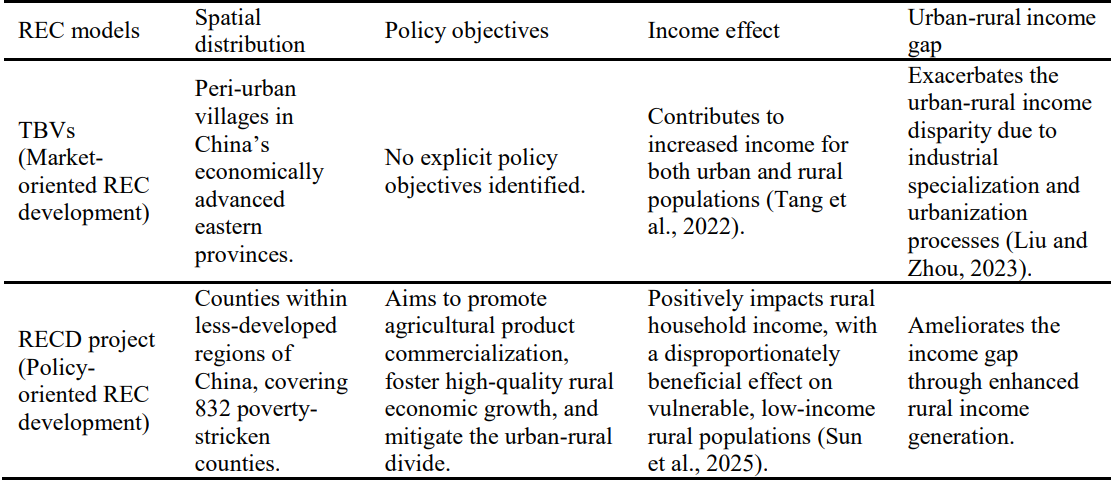

Table 1. Comparison of Taobao Villages and the RECD project

Notes: This table contrasts two models of rural e-commerce. Taobao Villages, emerging organically in peri-urban eastern provinces, boosted incomes but widened disparities. By contrast, the policy-driven RECD project targeted disadvantaged counties, raised rural household incomes, and reduced the urban-rural income gap.

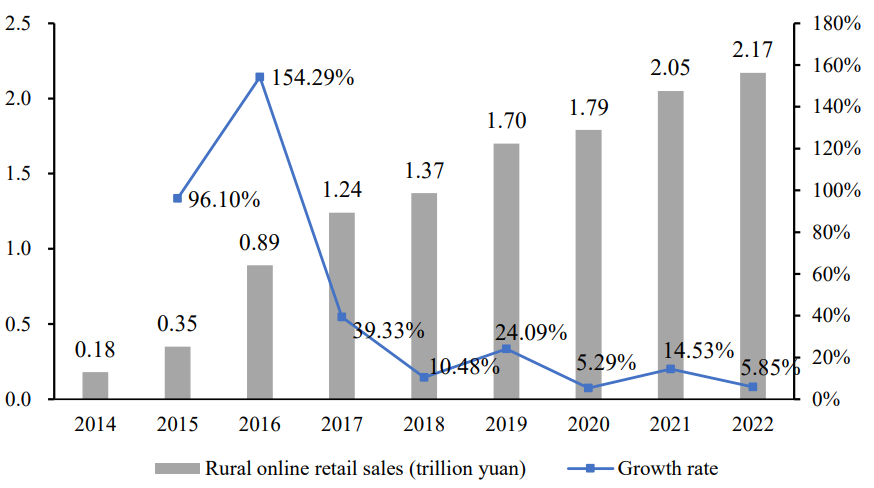

To address this question, our recent study turns to China’s “Rural E-Commerce Comprehensive Demonstration” (RECD) project, launched in 2014. Unlike TBVs, the RECD project is a top-down initiative that deliberately targets less-developed and poverty-stricken counties. Following an initial pilot phase that identified replicable models based on existing REC infrastructure, the project strategically prioritized less developed regions, particularly officially designated poverty counties, between 2015 and 2019. During this period, selection criteria favored nationally recognized poverty counties meeting specific developmental needs. As a result, the spatial distribution of the RECD pilot counties is heavily skewed towards China’s less developed central and western regions (Figure 1). Its design is ambitious: establishing county-level logistics hubs and village service stations, subsidizing training in digital skills, and promoting the sale of local agricultural products. Backed by over 20 billion yuan in funding from the central government, the program created more than 2,700 county-level centers and 1.58 million village-level stations by 2022, reducing “last-mile delivery” barriers and generating an eleven-fold increase in rural online sales between 2014 and 2022.

Figure 2. Rural online retail sales, 2014–2022

Notes: Rural online retail sales expanded more than elevenfold between 2014 and 2022, rising from 0.18 trillion yuan to 2.17 trillion yuan. The surge coincides with the rollout of the RECD project, which created logistics hubs and service stations that reduced “last-mile delivery” barriers.

Drawing on county-level data from 2006 to 2022, we employ a time-varying difference-in-differences framework to evaluate the RECD’s impact on the urban-rural income gap (Ji et al., 2023, Wei et al., 2024). The results are striking. On average, counties participating in the program experienced a 0.079 reduction in the ratio of urban-to-rural incomes relative to non-participating counties. Our regression results remain robust under a series of robustness checks. Furthermore, this effect is especially pronounced in less-developed regions, poverty-designated counties, and areas with weak digital infrastructure. In short, while market-driven REC has often heightened inequality, policy-driven REC has measurably narrowed the divide.

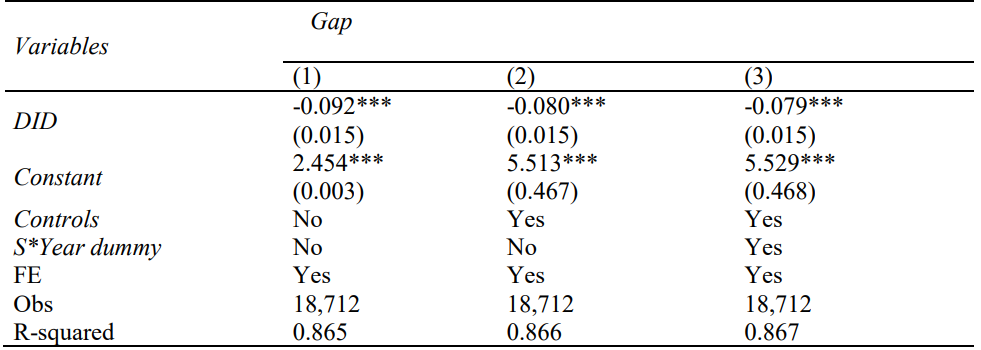

Table 2. Effect of RECD on the urban-rural income gap

Notes: This table reports baseline regression results. Participation in the RECD project reduced the urban-rural income ratio by 0.079 on average, confirming that targeted, policy-driven e-commerce development narrowed income disparities across counties.

Understanding how this happens is crucial. Our mechanism analysis shows that the RECD program generates what we term “skewed digital dividends.” Specifically, rural residents experience disproportionately greater gains in both income and employment. Rural household incomes increased by about 1.3% on average, while the impact on urban incomes was negligible. At the same time, rural employment rates rose by 2.2%, driven by new opportunities in logistics, warehousing, and online sales, whereas urban employment saw no significant change. These biased income and employment effects explain why the program reduces the income gap rather than exacerbating it.

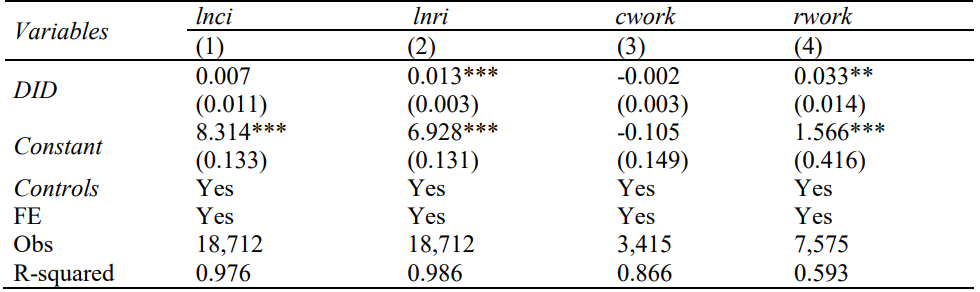

Table 3. Mechanisms: Income and employment effects

Notes: This table shows the “biased” digital dividends of the RECD project. Rural household incomes rose by about 1.3% and rural employment rates increased by 3.3%, while corresponding urban gains were negligible. These asymmetric benefits explain why the program narrowed the income gap.

The policy’s impact is also visible in case studies. In Jiangyong County, Hunan Province, local farmers were able to market specialty products such as pomelos and taro online, generating over 230 million yuan in sales and boosting household incomes by 4,000 yuan annually. In Zhenxiong County, Yunnan Province, the program directly created more than 3,000 jobs and engaged hundreds of thousands of rural workers in related activities. These examples illustrate how targeted support for agricultural e-commerce can empower rural residents, raise incomes, and absorb surplus labor.

Our analysis further examines how the RECD interacts with other rural policies. We find strong complementarities with rural information initiatives that establish information service stations, improve connectivity, and provide training. Where these programs are present, the RECD’s impact on narrowing the income gap is amplified. In contrast, synergy with the Broadband China policy is limited, reflecting that program’s urban bias. The Rural Returning Entrepreneurship policy even offsets some of the RECD’s gains, as its benefits are often captured by local elites, highlighting the risk of unequal resource allocation in policy design.

Taken together, these findings suggest that the design of digital policies matters greatly. Left to market forces, REC can cluster in better-off regions and widen disparities. By contrast, when carefully targeted to disadvantaged counties, supported by infrastructure investment, and combined with complementary information policies, REC becomes a powerful tool for inclusive growth.

The broader implications extend beyond China. Many developing economies face similar challenges of regional inequality and limited rural market access. The Chinese experience demonstrates that digital technologies alone are not enough; deliberate public policy is required to ensure that their dividends reach the poorest communities. The RECD project shows that when the state lowers entry barriers, invests in logistics and digital skills, and builds supportive ecosystems, e-commerce can be a bridge rather than a barrier between urban and rural societies.

References

Ji, X., Xu, J., Zhang, H., 2023. Environmental effects of rural e-commerce: A case study of chemical fertilizer reduction in China. Journal of Environmental Management 326, 116713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.116713

Juhász, R., 2018. Temporary Protection and Technology Adoption: Evidence from the Napoleonic Blockade. American Economic Review 108, 3339–3376. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20151730

Liu, Y., Zhou, M., 2023. Can rural e-commerce narrow the urban–rural income gap? Evidence from coverage of Taobao villages in China. CAER 15, 580–603. https://doi.org/10.1108/CAER-09-2022-0221

Sun, Y., Yuan, Y., Wang, L., 2025. Build or Break? The Impact of Rural E‐Commerce on Household Income Inequality in China. Review Development Economics rode.13221. https://doi.org/10.1111/rode.13221

Tang, K., Xiong, Q., Zhang, F., 2022. Can the E-commercialization improve residents’ income? --Evidence from “Taobao Counties” in China. International Review of Economics & Finance 78, 540–553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iref.2021.12.019

Tang, W., Zhu, J., 2020. Informality and rural industry: Rethinking the impacts of E-Commerce on rural development in China. Journal of Rural Studies 75, 20–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.02.010

Wei, B., Zhao, C., Luo, M., 2024. Online markets, offline happiness: E-commerce development and subjective well-being in rural China. China Economic Review 87, 102247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2024.102247

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email