Returnees and Innovation: Evidence from Chinese Publicly Listed Firms

We investigate the relationship between high-skill returnees and innovation of Chinese publicly listed firms. To this aim, we construct a unique dataset of 2,499 firms over the period 2002–2016 by combining three different data sources (i.e. CNRDS, CSMAR, and LinkedIn). Our results show that different typologies of returnees (employees, technologists, and managers) with different experiences abroad (work versus study) may bring back different skills and impact differently on firm innovation.

Cross-border flows of high-skill migrants have become an important channel for international knowledge diffusion and innovation (OECD 2018; Breschi et al. 2020). The impact of global talent has been observed in advanced economies, most notably in the US (Kerr et al. 2016), as well as in emerging economies (Kenney, Breznitz, and Murphree 2013), including China. For example, in the Zhongguancun Science Park, China’s first state-led industrial development zone, around a quarter of high-tech enterprises are founded by returnee entrepreneurs (Li and Xu 2011). In recent decades, returnees have played an important role in the Chinese long-term strategy of becoming a world technological leader: the capital, technology, and managerial knowledge brought back by returnees have helped Chinese companies grow and modernize.

We investigate the relationship between Chinese returnees and the innovation performance of Chinese publicly listed firms in our recent working paper (Qiao et al. 2023). Most of the existing evidence on high-skill returnees has focused on academic scientists and entrepreneurs (Filatotchev et al. 2011, Khan and MacGarvie 2020, Wadhwa et al. 2009), while the firm-level implications of returnees have thus far received only limited attention. Moreover, empirical studies using firm-level data have mostly examined the impact of CEOs and senior managers on firm productivity rather than innovation. Overall, the literature has largely overlooked the role of different typologies of returnees, other than managers, despite their relevance.

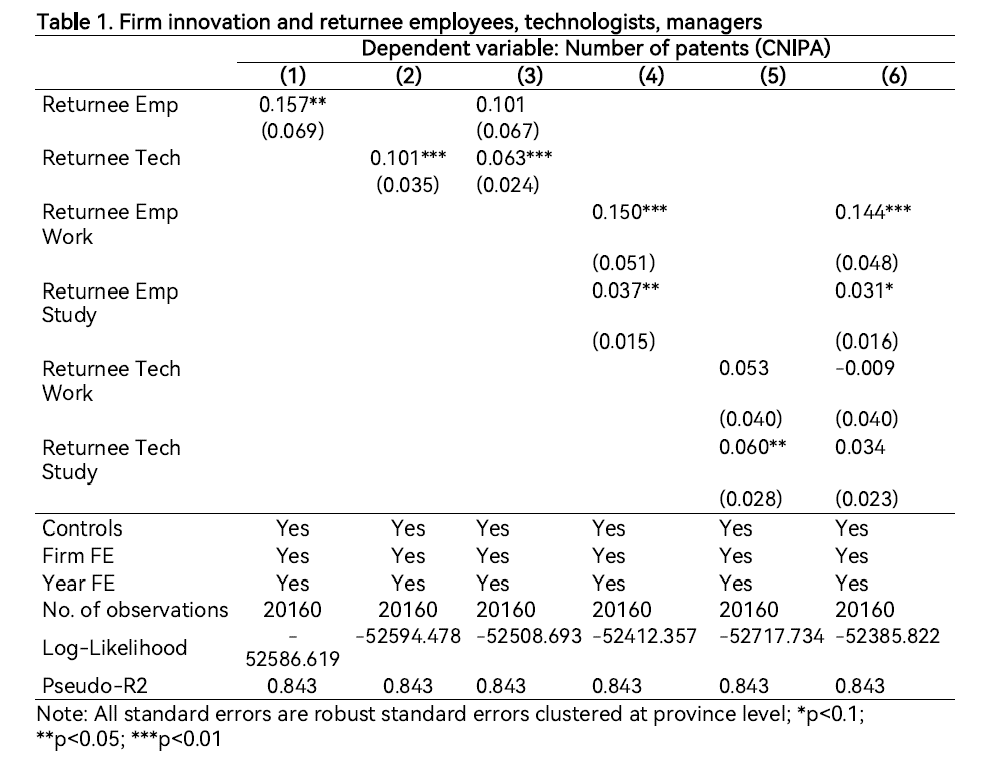

This study contributes to the extant literature in two ways. First, it brings to the forefront the importance of returnees within companies, in particular their impact on corporate innovation performance. Second, it disentangles the role of the different types of returnees, in terms of both their professional profiles (i.e., managers, employees, technologists) and the nature of the experience they accumulated while abroad (i.e., work versus study). The empirical analysis rests on an original dataset that combines three different sources: the Chinese Research Data Services Platform (CNRDS), the China Stock Market & Accounting Research (CSMAR) Database, and LinkedIn. From CNRDS, we consider the number of patent applications made by Chinese publicly listed companies at the China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA, known as SIPO before 2018). From CSMAR, we obtain detailed information on the overseas experience of managers and board members of Chinese publicly listed companies. From LinkedIn, we extract information on returnee employees and technologists in Chinese listed companies. Our dataset enables us to explore the diverse roles of returnees in a more comprehensive way than relying solely on data about returnee CEOs and managers. Considering the count character of our dependent variable, we use a Poisson regression framework in our empirical analysis. The dependent variable is the number of patents applied by firms, and the key explanatory variables are the percentage of different categories of returnees in the total number of employees.

Our main findings suggest the following:

(i)The numbers of “returnee employees” and “returnee technologists” are positively and significantly associated with firm innovation in general. Going to the details, we find that one unit increase of the coefficient of returnee employees (0.22%) is associated to a 17.00% increase in patent applications. As far as the impact of returnee technologists is concerned, we find that one unit increase (0.08%) leads to a 10.63% increase in patents. The large and significant impact of returnee employees, who bring also generic skills to domestic firms, generate spillovers that add up to the contribution made by returnee technologists. This suggests that working abroad is beneficial by itself, and not limited to knowledge brought by workers who had specific job profiles.

(ii)There is no impact of “returnee managers” on corporate innovation. However, when we replace our dependent variable, which is built on Chinese patents, with foreign patents (Chinese patents registered at the USPTO), returnee managers impact positively on firm innovation, while this is not the case for returnee employees and technologists. These findings seem to indicate some complementarity between the different types of returnees. Returnee employees and technologists apparently bring competencies that are relevant for innovations that are patented in the Chinese domestic market. Instead, returnee managers’ overseas experience becomes crucial once the company sets up a patenting strategy in the US. Patenting internationally is a critical corporate decision, especially for Chinese companies operating prevalently in the domestic market, and it requires skills that returnee managers (rather than employees) might have developed.

(iii)Overall, overseas work experience matters more than education abroad. In particular, results suggest that returnee employees and technologists with overseas work experience are positively associated with innovation. In details, a one standard deviation increase in returnee employees and returnee technologists with overseas work experience is associated with 15.49% and 3.15% increases in patent applications, respectively.

(iv)Results are heterogeneous across regions and firm ownership: returnees’ positive effect on firm innovation is mainly observed in large state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and in Eastern regions. This reflects the idiosyncratic and contextual factors of a country like China, which has a strongly regulated economy where the state exerts direct control on firm governance and ultimately on innovation strategies and where there is also a strong regional divide between coastal and inner areas. In particular, the positive impact of returnees in SOEs reflects the SOEs’ high social status, that returnees have a stronger impact within organizations where there is more room for efficiency improvements (as it usually happens in SOEs). We also show that SOEs are not more innovative than private firms. Innovative SOEs are the subset of SOEs that attract return migrants (either employees or technologists).

Table 1. Firm innovation and returnee employees, technologists, managers

In our empirical analysis, we use a comprehensive set of control variables, fixed effects, and lagged independent variables to reduce problems of reverse causality and endogeneity. Indeed, we can expect returnees to move to firms that offer better employment opportunities, which may include those that perform better in terms of innovation. Therefore, any causal implication from our results should be taken with caution. With this in mind, we can illustrate some of the policy implications that can be drawn from our research.

First, since returnees matter for firm innovation, in particular in SOEs, Chinese central and local governments, which have implemented several preferential policies to attract returnees, may decide to extend these schemes. Returnees, in fact, may help the less dynamic actors in the domestic market, such as SOEs, upgrade and innovate.

Second, depending on their innovation strategies, firms could aim to attract different types of returnees (Wright et al. 2008, Wang et al. 2018, Giannetti et al. 2015, Yuan and Wen 2018), since returnee employees (and technologists) are more important for domestic patenting and returnee managers for international patenting. Importantly, returnee managers seem to favor the internationalization of firms’ patenting activities, in line with previous evidence on this topic (Choudhury 2016).

Third, returnees with overseas work experience generally contribute more than those with only overseas study experience. This suggests that policies should possibly target this group (Saxenian 2006). More generally, this finding questions those policies aimed at preventing brain-drain by forcing students to return home immediately after their studies abroad. Our findings suggest that it is the work experience (and possibly the social networks established during the overseas work experience) that makes the difference in terms of the returnees’ contributions once they are back.

References

Breschi, Stefano, Cornelia Lawson, Francesco Lissoni, Andrea Morrison, and Ammon Salter. 2020. “STEM Migration, Research, and Innovation.” Research Policy 49 (9): 104070. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2020.104070.

Choudhury, Prithwiraj. 2016. “Return Migration and Geography of Innovation in MNEs: A Natural Experiment of Knowledge Production by Local Workers Reporting to Return Migrants.” Journal of Economic Geography 16 (3): 585–610. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbv025.

Filatotchev, Igor, Xiaohui Liu, Jiangyong Lu, and Mike Wright. 2011. “Knowledge Spillovers through Human Mobility Across National Borders: Evidence from Zhongguancun Science Park in China.” Research Policy 40 (3): 453–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2011.01.003.

Giannetti, M., Liao, G., & Yu, X. (2015). The brain gain of corporate boards: Evidence from China. the Journal of Finance, 70(4), 1629-1682.

Kahn, Shulamit, and Megan MacGarvie. 2020. “The Impact of Permanent Residency Delays for STEM PhDs: Who Leaves and Why.” Research Policy 49 (9): 103879. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2019.103879.

Kenney, Martin, Dan Breznitz, and Michael Murphree. 2013. “Coming Back Home After the Sun Rises: Returnee Entrepreneurs and Growth of High-Tech Industries.” Research Policy 42 (2): 391–407. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2012.08.001.

Kerr, Sara Pekkala, William Kerr, Çağlar Özden, and Christopher Parsons. 2016. “Global Talent Flows.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 30 (4): 83–106. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.30.4.83.

Li, P., and Xu, J. 2011. “On the Diffusion Effect of Intellectual Returnees: An Analysis Based on Regional Differences and Threshold Characters in China [J].” China Economic Quarterly 10 (2): 935–64. [In Chinese]

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. 2018. Education at a Glance 2018: OECD indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Qiao, Yibo, Andrea Ascani, Stefano Breschi, and Andrea Morrison. 2023. “Returnees and Innovation: Evidence from Chinese Publicly Listed Firms.” https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4483030.

Saxenian, A. (2006). The new argonauts: Regional advantage in a global economy. Harvard University Press.

Wadhwa, Vivek, AnnaLee Saxenian, Richard B. Freeman, and G. Gereffi. 2009. “America’s Loss Is the World’s Gain: America’s New Immigrant Entrepreneurs, Part 4.” https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1348616.

Wang, Xu, Zhuan Xie, Xiaobo Zhang, and Yiping Huang. 2018. “Roads to Innovation: Firm-Level Evidence from People's Republic of China.” China Economic Review 49: 154–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2017.12.012.

Wright, Mike, Xiaohui Liu, Trevor Buck, and Igor Filatotchev. 2008. “Returnee Entrepreneurs, Science Park Location Choice and Performance: An Analysis of High-Technology SMEs in China.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 32 (1): 131–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2007.00219.x.

Yuan, Rongli, and Wen Wen. 2018. “Managerial Foreign Experience and Corporate Innovation.” Journal of Corporate Finance 48: 752–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2017.12.015.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email