Financing Micro-entrepreneurship in Online Crowdfunding Markets: Local Preference versus Information Frictions

Crowdfunding has become an important financing alternative for micro-entrepreneurship. We study to what extent bias toward local entrepreneurs is prevalent in crowdfunding markets, determine the main driving forces for such bias, and examine how crowdfunding platforms and policymakers can leverage these forces to stimulate micro-entrepreneurship. Even though online crowdfunding platforms are designed to overcome geographic barriers, we find evidence of strong local bias induced by both informational frictions and local preference, with the former being more important.

Micro-entrepreneurship is an important source of job creation, innovation, and hence long-term growth in an emerging economy (Bruton et. al., 2015; Jayachandran, 2020). Credit or capital access plays a vital role in promoting such entrepreneurship (Bao et. al., 2018). For example, government agencies in China were known to court potential investors vigorously, especially those with roots in their own regions. Over the last decade, online crowdfunding marketplaces have become an important financing alternative for micro-entrepreneurship. These crowdfunding platforms enable entrepreneurs and funders to interact with fewer geographic constraints (Agrawal et al., 2015; Lin & Viswanathan, 2016). However, information asymmetry and preferences toward local projects may still persist in such online markets. These frictions induce biases toward local funding opportunities (Agrawal et al., 2014; Zhang & Liu, 2012) and discourage funders from identifying and investing in potentially high-quality projects outside their regions. In our recent working paper (Ni & Xin, 2020), we investigate whether local biases exist, and if they do, the channels through which they are induced in online crowdfunding marketplaces and how to mitigate them.

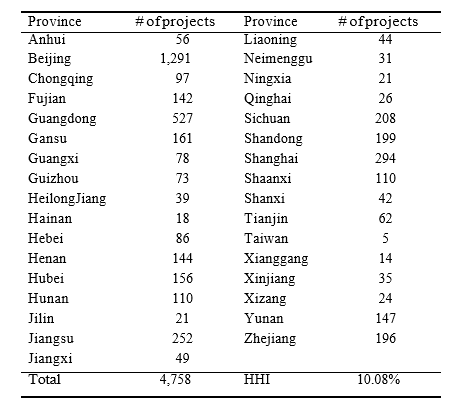

In our study, we collect the listings from one of the largest reward-based crowdfunding marketplaces in China from March 2013 to February 2017 (see Note 1). On the platform, small entrepreneurs propose various projects (such as selling agricultural products, developing video games, etc.) to raise funds. Our data include project-level characteristics and information on funders associated with each project (see Note 2). In the data, location information is available for most of the projects. The number of projects from each province is provided in the table below; we find a relatively low degree of geographic concentration for projects in this online crowdfunding market. We focus on the group of funders whose location information is available, which enables us to explore whether investors are more likely to contribute to projects in their home region. In the paper, we highlight two possible channels through which local biases are induced. First, funders may have some inherent “taste” for projects from their hometown, which may stem from local social networks (such as having common friends, knowing the relatives of the entrepreneur, or attending the same school, etc.) or be related to other non-pecuniary factors. Second, funders may have informational advantages if the projects are from their own region. For example, funders may be more familiar with the local environment and specialty products, which helps them to better assess the quality of the proposed project. Using different classification methods, including some text mining techniques (Gentzkow et al., 2019), we classify projects into two groups: Location-Related (LR) projects versus Non-Location-Related (NLR) projects. We then estimate a structural model of agents' investment behavior in online crowdfunding markets, allowing both the preference and the information channels.

Table: Number of Projects from Each Province

Our identification of the preference channel comes as follows. For non-location-related projects (e.g., producing music albums, developing software packages etc.), which do not rely heavily on the local environment and specialties, the information channel may not play an important role. Comparing investment behavior between funders from the same or different regions for these projects identifies the preference channel. The identification of the information channel follows a difference-in-difference (DID) analog. If the preference toward local projects is the same for the control (non-location-related projects) and the treatment groups (location-related projects), the additional local bias observed for location-related projects pins down the importance of the information channel.

We find evidence of strong local bias among funders in this online crowdfunding marketplace: funders are significantly more likely to invest in projects that are from the same region, all else being equal. With the structural estimates, we quantify the importance of information asymmetry and preference toward local projects on inducing local biases. For location-related projects, when we remove the information advantages for same-province investors (see Note 3), the probability that a project is successfully funded decreases from 76.29% to 70.02%, and more than 50% of the projects do not have any funders from the same region. Further shutting down the preference channel (i.e., assuming there is no extra utility gain from investing in same-region projects) leads to an additional decrease in the funding rate (to 66.65%). As for the numbers of funders, for location-related projects, the information channel accounts for 53.51% of the decrease in the number of same-region funders, and 46.49% is attributed to the preference channel.

Micro-entrepreneurship in emerging markets is often related to location-related projects (e.g., producing agricultural products). It is generally difficult for outside investors to evaluate the quality of the projects if no further information is provided. Policy interventions, such as subsidies to marketing agricultural products, educating microentrepreneurs to provide more detailed project descriptions, subsidies for sending samples of location-related products, or facilitating communications between funders and entrepreneurs (e.g., organizing online Q&A sessions, developing tools for instant messaging, etc.) may reduce information asymmetry between entrepreneurs and funders, thus stimulating these local entrepreneurial activities. We evaluate the effectiveness of such policy interventions that aim to promote local entrepreneurship in a counterfactual experiment, where the investor’s uncertainty about the product quality is reduced. Our results suggest that reducing information frictions has a sizable impact: for location-related projects, there is a 55.18% increase in the number of projects invested per person when the friction is reduced. If we reduce information frictions for all projects, the number of cross-province investment is significantly increased by 1.0758 (the investors on average contribute to two projects in our data). Overall, investors are more willing to fund the project when there is less information friction, and the funding rate can increase to 85.91% if information frictions are reduced for all projects. Our results suggest that providing information about the projects through marketing might be a more efficient way to raise funds for micro-entrepreneurship as it mitigates non-local funders' informational disadvantages.

Note 1: Different from equity-based or debt-based crowdfunding, in reward-based crowdfunding, entrepreneurs pre-sell a product or a service to launch their businesses without incurring debt or sacrificing equity. Examples of reward-based crowdfunding platforms in the US include Kickstarter and Indiegogo.

Note 2: For each project, we observe the amount requested by the entrepreneur, project descriptions, whether the entrepreneurs’ identities have been verified, etc. We also observe the amount contributed by each funder to a specific project (as well as the time at which the contribution was made).

Note 3: In this counterfactual exercise, we assume that the quality signals the investors receive are the same no matter where the investors are from.

(Jian Ni, Johns Hopkins University; Yi Xin, California Institute of Technology)

References

Agrawal, Ajay, Christian Catalini, and Avi Goldfarb. 2014. “Some Simple Economics of Crowdfunding.” Innovation Policy and the Economy, 14(1): 63–97.

Agrawal, Ajay, Christian Catalini, and Avi Goldfarb. 2015. “Crowdfunding: Geography, Social Networks, and the Timing of Investment Decisions.” Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 24(2): 253–274.

Bao, Weining, Jian Ni, and Shubhranshu Singh. 2018. “Informal Lending in Emerging Markets.” Marketing Science, 37(1): 123–137.

Bruton, Garry, Susanna Khavul, Donald Siegel, and Mike Wright. 2015. “New Financial Alternatives in Seeding Entrepreneurship: Microfinance, Crowdfunding, and Peer-to-peer Innovations.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(1): 9–26.

Gentzkow, Matthew, Bryan Kelly, and Matt Taddy. 2019. “Text as Data.” Journal of Economic Literature, 57(3): 535–574.

Jayachandran, Seema. 2020. “Microentrepreneurship in Developing Countries.” Working Paper, Northwestern University.

Lin, Mingfeng, and Siva Viswanathan. 2016. “Home Bias in Online Investments: An Empirical Study of an Online Crowdfunding Market.” Management Science, 62(5): 1393–1414.

Ni, Jian and Xin, Yi, 2020. “Financing Micro-Entrepreneurship in Online Crowdfunding Markets: Local Preference versus Information Frictions.” Johns Hopkins Carey Business School Research Paper No. 20-09, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3580585 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3580585.

Zhang, Juanjuan, and Peng Liu. 2012. “Rational Herding in Microloan Markets.” Management Science, 58(5): 892–912.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email