Lucky Dragons

This article explores the intriguing connection between Chinese zodiac signs and parental investment in children’s development. Particularly, parents invest more in children born under the “lucky” sign of the dragon, potentially impacting their cognitive and noncognitive skills alike.

On February 10, 2024, the Year of the Dragon began according to the Chinese lunar calendar. Considered a lucky sign, the dragon is one of the twelve zodiac animals. In East Asian cultures, many believe the tiger also offers similar fortune, leading some parents to plan their children’s births around these years (Lim 2012). This extends to Asian immigrants in the United States (Johnson and Nye 2011). Reflecting this belief, China’s birth ratio in the middle eight months of recent dragon years (1976, 1988, and 2000) is significantly higher (0.697) than in other lunar years (0.675). In 2000 alone, an estimated 391,000 more children were born during those months. So, with the 2024 dragon year, a new wave of “dragon babies” is anticipated. An interesting question arises: do parents invest more in these “lucky” children, and do they perform better in terms of cognitive and noncognitive skills compared to their peers born under less auspicious signs?

Our study (Tan, Wang, and Zhang 2024) delves into the fascinating world of astrology and its potential impact on parenting. Our research explores how zodiac signs, particularly auspicious symbols like the dragon, might shape parental investment and, consequently their children’s development. There are at least two potential channels. The first channel is superstition. Rooted in the cultural beliefs of East Asia, particularly China, some parents harbor strong convictions about the future prospects of children born under specific (lucky) zodiac signs. These beliefs, according to Mocan and Yu (2020), translate into higher expectations and, consequently, greater investments in these children’s education. This increased support, in turn, could lead to improved academic outcomes and success—creating a self-fulfilling prophecy of sorts.

The second channel is social pressure. Believing in the potential fortune associated with certain zodiac signs like the dragon, some parents allocate more resources to their children’s upbringing. This creates a ripple effect, influencing even non-superstitious parents to increase their investment through a “social interaction effect” (Durlauf and Ioannides 2010; Blume et al. 2011). In this scenario, the decisions of superstitious parents shape the actions of others, regardless of their personal beliefs. Notably, whether driven by superstition or social pressure, the predicted outcome remains the same: parents invest more in children born under auspicious zodiac signs.

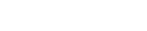

Testing this prediction isn’t straightforward because some parents time their children’s birth to lucky years like the dragon. This introduces a bias, as these parents might already be predisposed to invest more in their children with lucky zodiac signs. This group of parents may have a particular preference for investing in their children. To overcome this hurdle, we focus on children whose zodiac signs are effectively random. We consider a child’s sign random only if their birthdate falls within two months of the sign’s boundary (Figure 1). This “regression discontinuity” approach allows us to compare investment and skill development between children born around the same time but with different lucky signs. By doing so, we can isolate the true impact of the zodiac sign on parental investment and child development.

The study draws data from the child survey module in the 2010, 2012, and 2014 waves of the China Family Panel Studies. Parental investment is proxied by educational cost. Cognitive skills include word recognition and mathematical ability, while noncognitive skills are measured by curiosity, organization, optimism, mistake tolerance, and anger control. The number of observations slightly differ between the two samples.

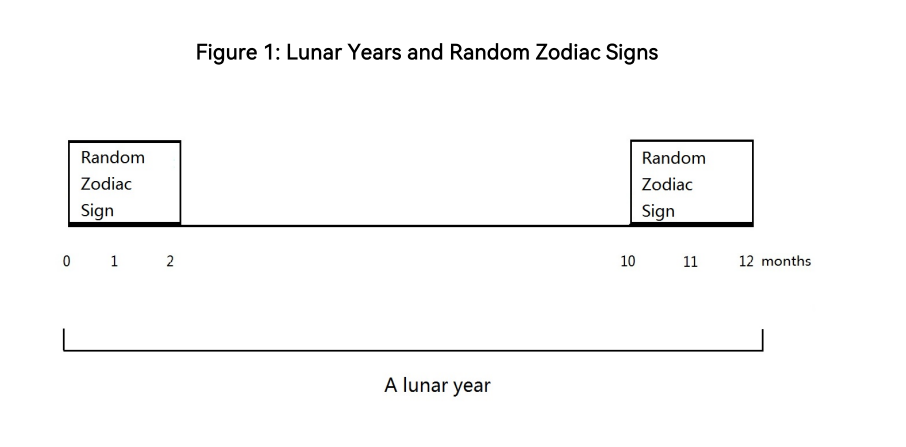

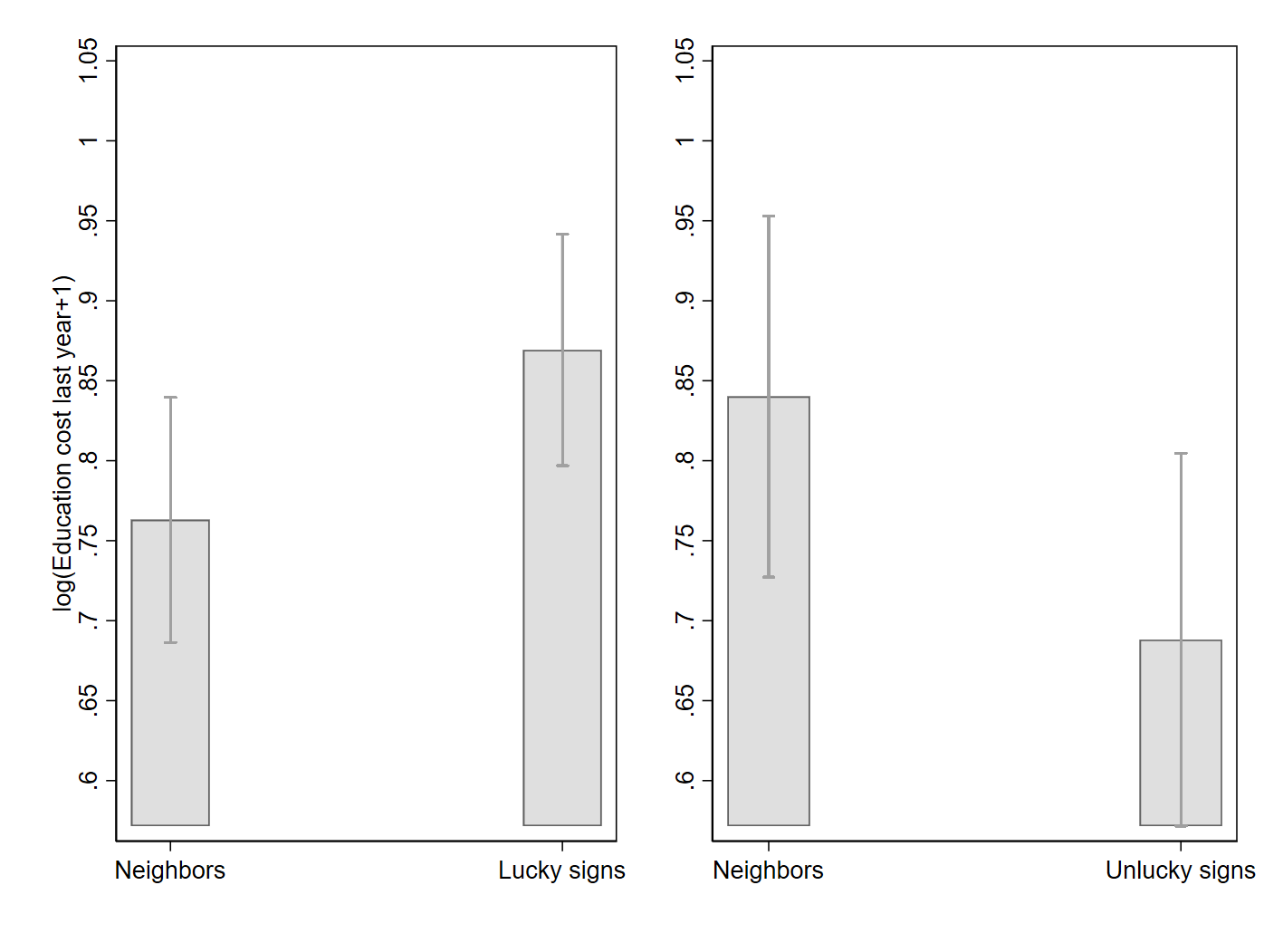

Figures 2 and 3, respectively, compare parental investment levels for children with lucky and unlucky zodiac signs and their adjacent random zodiac signs in the sample for cognitive and noncognitive skills. The two figures clearly show that parents invest significantly more in children with random lucky signs in both samples.

Figure 2: Random Zodiac Signs and Parental Investment

in the Sample for Cognitive Skills

Note: This figure depicts the average parental investments measured as mean log (education cost last year+1) between lucky random zodiac signs and their neighboring signs, and between unlucky random zodiac signs and their neighboring signs, in the sample for cognitive skills. The bars are means of logged education costs, and the lines on bars indicate plus/minus two standard deviations from the mean. The lucky random zodiac signs include early tiger (1998), late tiger (1999), early dragon (2000), and late dragon (2001); their neighboring signs include late ox (1998), early rabbit (1999), late rabbit (2000), and early snake (2001). The unlucky signs are early snake (2001), late snake (2002), and early sheep (2003); their neighboring signs are late dragon (2001), early horse (2002), and late horse (2003).

Figure 3: Random Zodiac Signs and Parental Investment

in the Sample for Noncognitive Skills

Note: This figure depicts the average parental investments measured as mean log (education cost last year+1) between lucky random zodiac signs and their neighboring signs, and between unlucky random zodiac signs and their neighboring signs, in the sample for noncognitive skills. The bars are means of logged education costs, and the lines on bars indicate plus/minus two standard deviations from the mean. The lucky random zodiac signs include late tiger (1999), early dragon (2000), and late dragon (2001); their neighboring signs include early rabbit (1999), late rabbit (2000), and early snake (2001). Early tiger (1998) and its neighboring sign late ox (1998) are not included due to no observations. The unlucky signs are early snake (2001), late snake (2002), early sheep (2003), and late sheep (2004); their neighboring signs are late dragon (2001), early horse (2002), late horse (2003), and early monkey (2004).

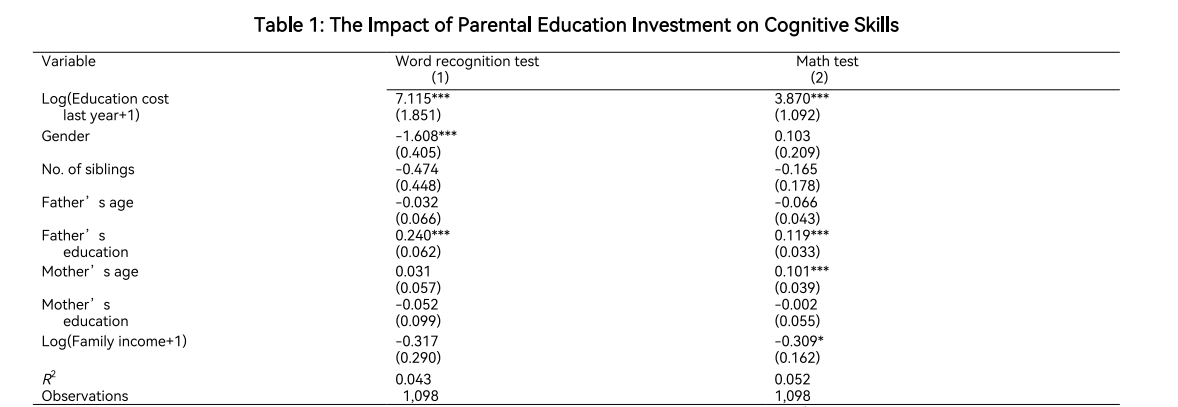

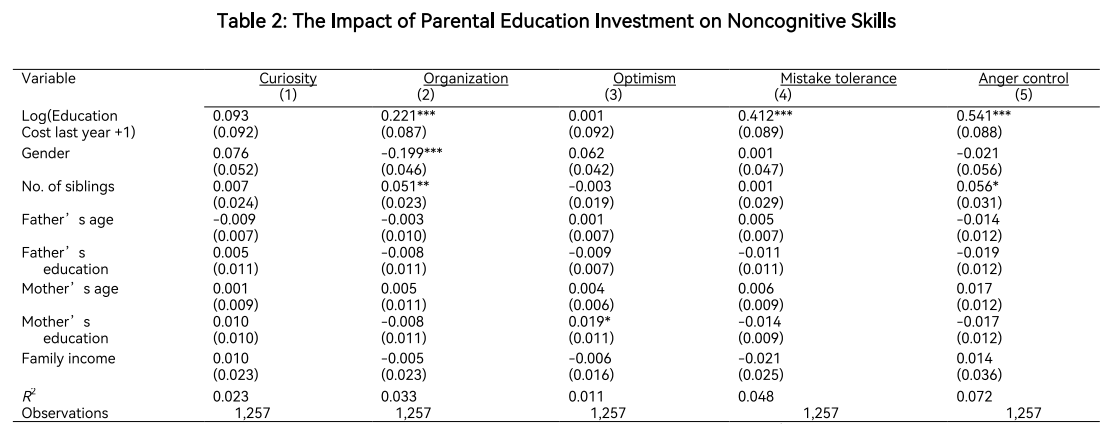

Building on the finding that parents invest differently in children with random lucky and unlucky zodiac signs compared to their neutral counterparts, we further explore the impact of their investment on children’s skill development. Tables 1 and 2 present the regression results on cognitive and non-cognitive skill measures, respectively.

Note: This table displays the

second-stage regression results for the impacts of parental investment on

children’s cognitive skills. The first-stage regression, omitted here, shows

that parents invest differently in children with random lucky (unlucky) zodiac

signs compared to their neutral counterparts. The sample includes all children

for whom cognitive skill test results are available (birth years 1997 through

2004) and who were born within the last two months or the first two months of a

lunar year. Appendix Table A.2 in Tan, Wang, and Zhang (2024) provides detailed

explanations for all variables. Children born in 2004 are used as the reference.

All regressions are clustered at children’s birth year-month levels. ***, **,

and * denote significance at 1%, 5%, and 10%, respectively.

Table 1 reveals a clear connection between parental investment and children’s cognitive skills. Higher educational spending significantly boosts children’s performance on word recognition and math tests. The impact is substantial. For example, a 10% increase in education expenditure raises a child’s word recognition test score, on average, by 0.712, or 9.5% of the standard deviation of this score (7.510). Similarly, a 10% increase in education expenditure raises the average math test score by 0.387, or 9.3% of a standard deviation of this score (4.182).

Note: This table displays the second-stage regression

results for the impacts of parental investment on children’s noncognitive

skills. The sample includes all children for whom noncognitive skill test

results are available and whose birth dates fall in the last or first two

months of a lunar year. Appendix Table A.2 provides detailed explanations for

all variables. All regressions are clustered at children’s birth year-month

levels. ***, **, and * denote significance at 1%, 5%, and 10%, respectively.

Similarly, as shown in Table 2, parental investment impacts children’s noncognitive skills. Increased spending cultivates valuable traits like curiosity, organization, tolerance for others’ mistakes, and anger control. This emphasizes the broader influence of parental investment beyond academics. In summary, the study demonstrates how deeply rooted cultural beliefs about zodiac signs can shape parental behavior, impacting children’s development in both cognitive and noncognitive domains.

References

Blume, Lawrence E., William A. Brock, Steven N. Durlauf, and Yannis M. Ioannides. 2011. “Identification of Social Interactions.” In Handbook of Social Economics, edited by Jess Benhabib, Alberto Bisin, and Matthew O. Jackson, 853–964. Amsterdam: North Holland. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-53707-2.00001-3.

Durlauf, Steven N., and Yannis M. Ioannides. 2010. “Social Interactions.” Annual Review of Economics 2: 451–78. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.economics.050708.143312.

Johnson, Noel D., and John V. C. Nye. 2011. “Does Fortune Favor Dragons?” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 78 (1–2): 85–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2010.12.010.

Kirchsteiger, Georg, and Alexander Sebald. 2010. “Investments into Education—Doing as the Parents Did.” European Economic Review 54 (4): 501–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2009.09.004.

Lim, Rebecca. 2012. “Enter the Dragons: A Baby Boom for Chinese across Asia.” BBC News, January 20, 2012. www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-16589052.

Mocan, Naci, and Han Yu. 2020. “Can Superstition Create a Self-Fulfilling Prophecy? School Outcomes of Dragon Children in China.” Journal of Human Capital 14 (4): 485–534.Ó https://doi.org/10.1086/712476.

Tan, Chih Ming, Xiao Wang, and Xiaobo Zhang. 2024. “It’s All in the Stars: The Chinese Zodiac and the Effects of Parental Investments on Offspring’s Cognitive and Noncognitive Skill Development.” Economics of Transition and Institutional Change, 1–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecot.12405.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email