How Liberalizing Trade with China Led to a Boom in International Students in the US

We highlight a lesser-known consequence of China’s integration into the world economy—the rise of services trade—demonstrating specifically how the US trade deficit in goods cycles back as a surplus in US exports of education services. Focusing on China’s accession to the World Trade Organization, we show that Chinese cities with more exposure to trade liberalization sent more students to US universities. Our estimates suggest that recent trade wars could cost US universities around $1.1 billion in annual tuition revenue.

When China joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) in December 2001, the United States saw hope for long-lasting economic gains from commerce with China. Today, that optimism feels fragile as a contentious trade war has yet to dissipate even under a new US administration. China’s rapid income growth, partly driven by its important role as “the world’s factory,” has met resistance from US policymakers who claim that significant trade barriers and unfair trade practices hinder US firms. Debates in the media and across political aisles in the US have focused on the concern that import competition has displaced American manufacturing workers (Autor, Dorn, and Hanson 2013). But interestingly, while US imports of goods continued to surge, exports of US services to China also grew (Bloom et al. 2019)—particularly higher education. As we discuss in a newly published paper (Khanna et al. 2023), a lesser-known consequence of trade liberalization is that more Chinese students have enrolled in US colleges and universities—delivering financial benefits to US schools. This is driven by the large export-driven wealth gains in China, especially at the high end of the distribution, which allow Chinese families to afford US tuition. If not addressed, mounting trade disputes and US plans to curtail student visas could cost US universities over $1 billion in lost revenue, with harmful ripple effects for US higher education and the broader economy.

The economic benefits of welcoming international students

US higher education has sustained tremendous growth in its “exports” overseas, meaning an increasing number of international students have come to the US to pursue undergraduate or graduate education in recent years. These students bring clear benefits to US schools: they are a valuable source of tuition revenues (Bound et al. 2020), allowing universities to maintain a high-quality educational experience and affordable tuition for local students (Shih 2017).

Unlike traditional delivery of exports, where products are sent and consumed in the destination country, international students come to US universities to consume education services. In doing so, they not only provide much-needed tuition revenue, but also local spending on other goods and services, A recent report by the Department of Commerce estimated that international students contributed over $30 billion to the US economy.

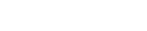

Chinese students have increased by over 500 percent, and account for over half of the total growth in international students in the United States from 2000 to 2018 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Number of new international students in the US by country of origin

Source: Open Doors, Institute for International Education, 1992–2018; includes graduate and undergraduate students.

The connection between exports and student migration

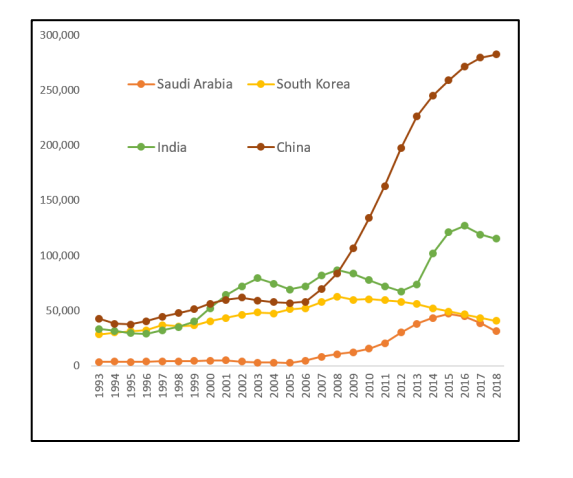

China’s accession to the WTO and the ensuing surge in goods exports (Figure 2) helped induce many Chinese students to study at US universities. Looking at cities across China, we link measures of trade liberalization exposure to the number of students leaving those cities to study in US universities. To measure exposure to trade liberalization at the city level, we leverage each city’s baseline composition of goods production along with variation across goods in the reduction in tariff uncertainty gained by joining the WTO.

Figure 2. Chinese exports, 1980–2017

Notes: This figure presents Chinese exports to the world as well as exports to the US only. Data for exports to the US are from Comtrade. Exports to the world are sourced from the World Bank. Both reflect exports in 2010 prices using the US GDP deflator for that year.

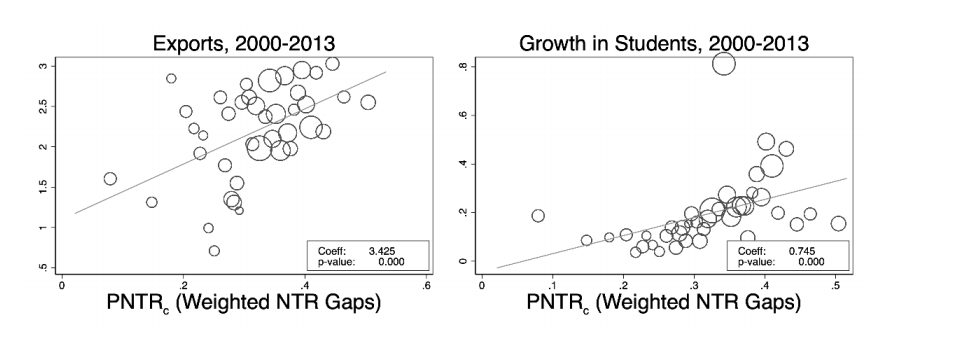

So for instance, if a city was a major producer of textiles, then the reduction in tariffs for textiles would have a much bigger impact there than in a city that relied more on, say, tobacco products. Figure 3 highlights the positive correlation between exposure to trade liberalization (PNTRc) and the growth of exports between 2000 and 2013 at the city level. Accordingly, we compare student flows to the US from cities where the WTO brought large reductions in tariff uncertainty against cities where the WTO created little to no change in export opportunities. This analysis is possible thanks to a unique combination of US and Chinese data: the universe of international student flows into the US with detailed information on city of origin linked to city-level Chinese exports derived from Chinese customs data. The US dataset is obtained from the Student and Exchange Visitor Information System (SEVIS) through a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request and includes records for every foreign student visa in the US by year of matriculation from 2000 to 2013, although we use only the records for students with origin in China.

Our findings show that trade liberalization dramatically increased the number of Chinese students studying in the US (Figure 4). The magnitude of the effect can be put into perspective by comparing it with secular trends in Chinese students going to the US. The 2002–13 period saw the flows of new Chinese students at US institutions increase from 12,500 per year to 98,500 per year (86,000 more new students per year). Our main findings imply that a yearly flow of approximately 35,000 Chinese students to the US can be attributed specifically to the exposure to reductions in tariff uncertainty. As such, the trade shock alone explains about 40% of the increase in the flow of Chinese international students in 2013 relative to the beginning of our sample. The reduced form finding captures various potential underlying mechanisms. The explanation we find the most support for is that export growth expanded the wealth of upper-income families, providing them with the means to finance the large cost of paying for housing and tuition in the US. Given limited investment opportunities in China, a meaningful fraction of this wealth expansion occurred through housing ownership—our evidence indicates that trade liberalization raised city-level housing prices and real estate income. Other mechanisms, such as changing returns to education or information flows, appear to play less of a role.

Figures 3 and 4. Responses of exports (left) and student enrollment in US universities (right) to city-level exposure to trade

Notes: Figures present binned scatter plots of exposure to trade liberalization (PNTRc) and growth in outcomes measured from 2000 to 2013. Plots show 40 equal-size bins, weighted by population size in each bin. Export growth is measured as the log change, using data from the China Customs Database. Student growth, constructed with SEVIS data, is measured as the change in the number of students leaving for US universities divided by the initial city population.

What our findings tell us about the relationship between migration and development

Our findings can inform discussions on the inverted-U shaped relationship between migration and development—that is, the observation that emigration initially rises with economic development, after which the relationship flips. While export growth and ensuing income/wealth expansions enable individuals to afford migration costs, they also may encourage individuals to remain at home and take advantage of better prospects. It is unclear, then, whether economic growth at home, induced by trade liberalization, would lead to more emigration. We resolve this ambiguity and introduce a new channel via which trade-induced income dynamics generate demand for certain types of services (like higher education), driving the flow of individuals across country borders. This is consistent with education being either an investment or a consumption good. As an investment, financially constrained households may respond to income increases by funding their education abroad. When education is a consumption good, increases in income reallocate expenditures toward services, like education.

The far-reaching impacts of a loss in US tuition revenues

Our results also speak to distributional impacts in US higher education. While Chinese students initially tended toward science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) majors and partially or fully funded doctoral programs, trade liberalization increased the number of Chinese students in social sciences and business-related majors and at the undergraduate level, where funding is minimal and full sticker-price tuition is required, generating more revenue for universities and helping keep tuition for US students down.

Foreign student tuition revenues and local demand are a crucial aspect of US services exports. But the ongoing trade wars with China and policy proposals to suspend or terminate student visas suggest a bleak future for international students hoping to study in the US. We use our findings to evaluate the consequences of the 2018 US-China trade war: the tariff increase of 20 percentage points in 2018 could cost US universities around 30,000 Chinese students in the next 10 years, a loss of $1.1 billion in tuition revenue, or 6 percent of educational services exports to China. This number does not reflect any further consequences to universities that might stem from the deterioration of US-China relations aside from tariffs specifically. The actual losses to higher education—an industry whose exports are about as large as the combined total exports of soybeans, coal, and natural gas—may likely be greater as continued threats of suspending various work visa programs, like the H-1B visa, and student visas loom.

References

Autor, David H., David Dorn, and Gordon H. Hanson. 2013. “The China Syndrome: Local Labor Market Effects of Import Competition in the United States.” American Economic Review 103 (6): 2121–68. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.103.6.2121.

Bloom, Nicholas, Kyle Handley, Andre Kurman, and Phillip Luck. 2019. “The Impact of Chinese Trade on US Employment: The Good, the Bad, and the Debatable.” Working Paper. https://conference.nber.org/conf_papers/f130843.pdf.

Bound, John, Breno Braga, Gaurav Khanna, and Sarah Turner. 2020. “A Passage to America: University Funding and International Students.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 12 (1): 97–126. https://doi.org/10.1257/pol.20170620.

Khanna, Gaurav, Kevin Shih, Ariel Weinberger, Mingzhi Xu, and Miaojie Yu. 2023. “Trade Liberalization and Chinese Students in US Higher Education.” Review of Economics and Statistics (forthcoming).

Shih, Kevin. 2017. “Do International Students Crowd-Out or Cross-Subsidize Americans in Higher Education?” Journal of Public Economics 156: 170–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2017.10.003.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email