Industrial Policy: Lessons from China

This paper examines an important industrial policy in China in the 2000s that aims to propel the country's shipbuilding industry to the largest globally. Using comprehensive data on shipyards worldwide and a dynamic model of firm entry, exit, investment, and production, we find that the scale of the policy was massive and boosted China's domestic investment, entry, and world market share dramatically. On the other hand, it created sizable distortions and led to increased industry fragmentation and idleness. The effectiveness of different policy instruments is mixed: production and investment subsidies can be justified by market share considerations, but entry subsidies are wasteful. Finally, the distortions could have been significantly reduced by implementing counter-cyclical policies and by targeting subsidies towards more productive firms.

Industrial policy, broadly defined as a policy agenda that shapes a country's or region's industrial structure by either promoting or restricting specific sectors, has been widely used in developed and developing countries. Historic examples of this kind of policy agenda include the U.S. and Europe after World War II, Japan in the 1950s and 1960s, and South Korea and Taiwan in the 1960s and 1970s. Today, industrial policy in the form of protectionism is once again at the forefront of economic policy in both the East and the West. As Rodrik (2010) proposes, “The real question about industrial policy is not whether it should be practiced, but how.”

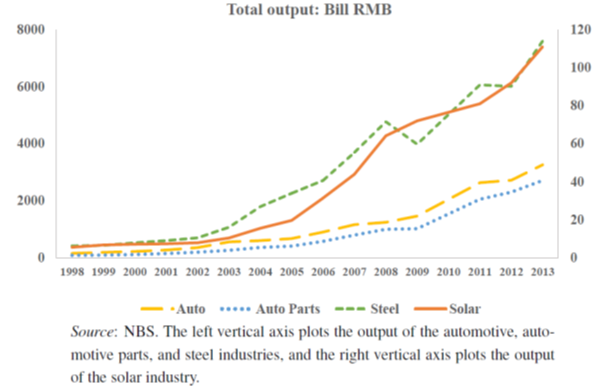

Despite the prevalence of industrial policy in practice and the contentious debate in the literature regarding its efficacy (Baldwin, 1969; Krueger, 1990), remarkably few empirical studies directly evaluate the costs and benefits of these policies. Our recent paper (Barwick, Kalouptsidi, and Zahur, 2019) addresses this issue, with a focus on China, where the regulatory agency has considerable influence over industry. During roughly the past two decades, Chinese firms have rapidly dominated many global industries, such as steel, automotive, and solar panels (Figure 1). In recent years, the government has explicitly targeted high-tech sectors in an attempt to turn their firms into world leaders (“Made in China 2025 ”).

Figure 1

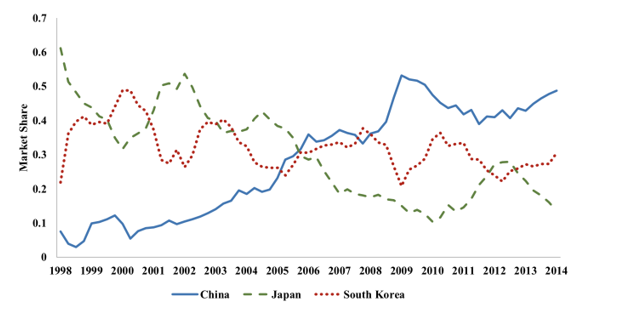

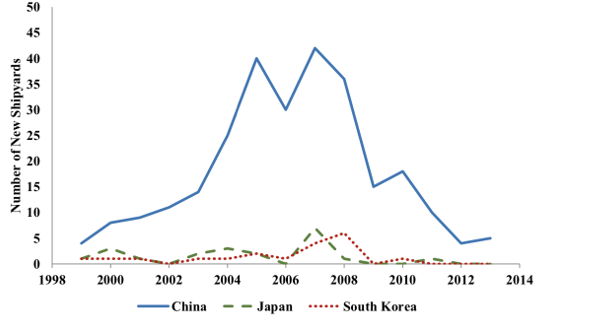

Our paper treats the shipbuilding industry as a case study. At the turn of the century, China’s nascent shipbuilding industry accounted for less than 10 percent of world production. The country’s 11th (2006–2010) and 12th (2011–2015) National Five-Year Plans dubbed shipbuilding a pillar industry in need of special oversight and support. Since then, the government issued an unprecedented number of national policies to develop this infant industry into the largest worldwide. The policies set specific goals for output and capacity and, as such, involved a mix of production, investment, and firm entry subsidies. (We discuss the possible motivations for these policies at the end of this article.) Production subsidies included input material and export credits, and buyer financing, among others. Investment subsidies took the form of low-interest, long-term loans and expedited capital depreciation. Finally, reduced processing time and simplified licensing procedures, as well as heavily subsidized land prices, significantly lowered the cost of entry for potential shipyards. Within a few years, China overtook Japan and South Korea as the leading ship producer in terms of output. Figures 2 and 3 depict the industry’s rapid expansion. In the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis and amidst a sharp decline in global ship prices, the government then promoted consolidation policies to create large, successful firms that can compete against international conglomerates.

Treating this historical event as a case study, we examine the consequences of industrial policies and focus on three questions: First, how has China’s industrial policy shaped its domestic and the global industry? Second, what are the costs and benefits of this policy? Third, what is the relative efficacy of various policy instruments, such as production subsidies, investment subsidies, entry subsidies, and consolidation policies?

Our analysis delivers four sets of main findings. First, like many other policies China’s central government has unleashed in recent decades, the scale of the industrial policy in the shipbuilding industry is massive (relative to the size of the sector), with the lion’s share of the subsidy going to entry subsidies. Our estimates suggest that the aggregate policy support from 2006 to 2013 is equivalent to RMB 550 billion (in nominal terms), with entry subsidies around RMB 330 billion, followed by production subsidies of RMB 159 billion and investment subsidies of RMB 51 billion.

The policy boosted China’s domestic investment and entry by 270 and 200 percent, respectively, and increased its world market share by 40 percent, three-quarters of which occurred via “business stealing” (i.e., reduced production) from rival countries. However, contrary to media reports that hailed this as a success, the policy created sizable distortions and generated mediocre net profit gains to domestic producers. Much of the subsidies was dissipated through the entry and expansion of unproductive and inefficient producers, which exacerbated the extent of excess capacity and did not translate into significantly higher industry profits in the long term.

Second, the policy instruments varied in their effectiveness. Production and investment subsidies can be justified on the grounds of revenue considerations, but entry subsidies are wasteful and lead to increased industry fragmentation and idleness. Specifically, entry subsidies attract small and high-cost producers; in contrast, production and investment subsidies favor large, efficient firms that benefit from economies of scale. Production subsidies achieve output targets more effectively, while investment subsidies are less distortionary over the long run. In addition, subsidy-induced distortions are “convex,” in that the combination of multiple subsidies induces firms to make further suboptimal decisions and yields returns that are considerably lower than would result from each policy in isolation.

Third, our analysis suggests that the efficacy of industrial policy is significantly affected by the presence of boom and bust cycles, as well as by heterogeneity in firm efficiency, both of which are essential features of the shipbuilding industry (see Kalouptsidi (2014), as well as Greenwood and Hanson (2015) for an account of these fluctuations). A counter-cyclical policy would have out-performed the pro-cyclical policy that was adopted by a large margin, whereby the effectiveness of raising long-term industry profit differs by nearly threefold. This is partly due to a composition effect (more high-cost firms survive during a boom than during a bust) and partly due to capacity constraints that render increases in production more costly during the boom. In a similar vein, had the government targeted subsidies to reach more efficient firms, the policy distortions would have been considerably lower.

Fourth, we examine the consolidation policy the government adopted in the aftermath of the financial crisis, whereby it implemented a moratorium on entry and issued a “White List” of firms selected to receive government support. Several industries adopted this strategy to curb excess capacity and create large conglomerates that can compete globally (see Note 1). Consistent with the evidence discussed above, we find that targeting low-cost firms creates fewer distortions; that said, the White List the government released favored state owned enterprises and did not include the most efficient firms. Finally, the gains from a policy package with entry subsidies (to overcome entry barriers and capital market inefficiencies) followed by a consolidation phase (to reduce fragmentation) are dwarfed by the cost of the subsidies and do not provide a compelling justification for implementing such a policy.

We explore a number of traditional rationales for industrial policy. We find limited evidence that the shipbuilding industry generates significant spillovers to the rest of the domestic economy (e.g., steel production, ship owning, and the labor market). Nor do we find evidence of industry-wide learning-by-doing (Marshallian externalities) or support for strategic trade considerations. In terms of the benefits to Chinese trade, the policy the government implemented in the shipbuilding industry may have lowered freight rates and boosted China’s imports and exports; however, evaluating the associated economic benefits is beyond the scope of this paper. Finally, it is worth noting that non-economic arguments—such as national security, military considerations, and the desire to be number one worldwide (Grossman 1990)—could be important for the design of this policy. Regardless of the motivation, our analysis provides cost estimates and the relative efficacy of implementing different policies that governments can use to guide future policies.

Note 1: See for an example, Chuin-Wei Yap and Paul Mozur, “China Aims to Create Electronics Giants,” Wall Street Journal, Jan. 22 2013. Accessed September 6, 2019, at https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424127887324624404578257351843112188

(Barwick,Department of Economics, Cornell University and NBER; Kalouptsidi, Department of Economics, Harvard University and NBER; Zahur,Department of Economics, Cornell University.)

References

Baldwin, Robert E. 1969. “The Case against Infant-Industry Tariff Protection.” Journal of Political Economy 77 (3): 295–305. URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1828905

Barwick, Panle Jia, Myrto Kalouptsidi, and Nahim Zahur. 2019. “China’s Industrial Policy: An Empirical Evaluation.” NBER working paper 26075, July. URL: https://docs.google.com/viewer?a=v&pid=sites&srcid=ZGVmYXVsdGRvbWFpbnxteXJ0b2thbG91cHxneDo2OTI4OWM2YTdjYjJhNzVh

Greenwood, Robin, and Samuel G. Hanson. 2015. “Waves in Ship Prices and Investment.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 130 (1): 55–109. URL: https://academic.oup.com/qje/article/130/1/55/2337948

Grossman, M. Gene. 1990. “Promoting New Industrial Activities: A Survey of Recent Arguments and Evidence.” OECD Economic Studies 14 (Spring). URL: https://search.oecd.org/eco/growth/34306065.pdf

Kalouptsidi, Myrto. 2014. “Time to Build and Fluctuations in Bulk Shipping.” American Economic Review 104 (2): 564–608. URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/42920708

Krueger, Anne O. 1990. “Government Failures in Development.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 4 (3): 9–23. URL: https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jep.4.3.9

Rodrik, Dani. 2010. “The Return of Industrial Policy.” Project Syndicate, 12 April. URL: https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/the-return-of-industrial-policy?barrier=accesspaylog

Yap, Chuin-Wei, and Paul Mozur. 2013. “China Aims to Create Electronics Giants.” Wall Street Journal, Jan. 22 2013. URL: https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424127887324624404578257351843112188

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email